The Godfather Part II

| The Godfather Part II | |

|---|---|

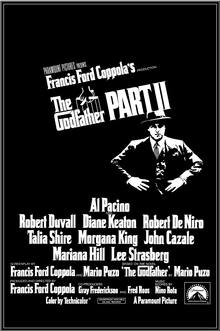

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Francis Ford Coppola |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | The Godfather by Mario Puzo |

| Produced by | Francis Ford Coppola |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Gordon Willis |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 202 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $13 million[2][3] |

| Box office | $93 million[N 1] |

The Godfather Part II is a 1974 American epic crime film produced and directed by Francis Ford Coppola, loosely based on the 1969 novel The Godfather by Mario Puzo, who co-wrote the screenplay with Coppola. It is both a sequel and a prequel to the 1972 film The Godfather, presenting parallel dramas: one picks up the 1958 story of Michael Corleone (Al Pacino), the new Don of the Corleone family, protecting the family business in the aftermath of an attempt on his life; the other covers the journey of his father, Vito Corleone (Robert De Niro), from his Sicilian childhood to the founding of his family enterprise in New York City. The ensemble cast also features Robert Duvall, Diane Keaton, Talia Shire, Morgana King, John Cazale, Marianna Hill and Lee Strasberg.

Following the first film's success, Paramount Pictures began developing a follow-up, with many of the cast and crew returning. Coppola, who was given more creative control, had wanted to make both a sequel and a prequel to The Godfather that would tell the story of Vito's rise and Michael's fall. Principal photography began in October 1973 and wrapped up in June 1974. The Godfather Part II premiered in New York City on December 12, 1974, and was released in the United States on December 20, 1974, receiving divisive reviews from critics; its reputation, however, improved rapidly, and it soon became the subject of critical re-appraisal. It grossed $48 million in the United States and Canada and up to $93 million worldwide on a $13 million budget. The film was nominated for eleven Academy Awards, and became the first sequel to win Best Picture. Its six Oscar wins also included Best Director for Coppola, Best Supporting Actor for De Niro and Best Adapted Screenplay for Coppola and Puzo. Pacino won Best Actor at the BAFTAs and was nominated at the Oscars.

Like its predecessor, Part II remains a highly influential film, especially in the gangster genre. It is considered to be one of the greatest films of all time, as well as a rare example of a sequel that rivals its predecessor.[4] In 1997, the American Film Institute ranked it as the 32nd-greatest film in American film history and it retained this position 10 years later.[5] It was selected for preservation in the U.S. National Film Registry of the Library of Congress in 1993, being deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[6] The Godfather Part III, the final installment in the trilogy, was released 16 years later in 1990.

Plot

[edit]The film interweaves events some time after The Godfather and the early life of Vito Corleone.

Vito

[edit]In 1901, in Corleone, Sicily, Mafia chieftain Don Ciccio kills the family of nine-year-old Vito Andolini after his father refuses to pay tribute. Vito escapes to New York City and is registered on arrival as "Vito Corleone" by an immigration officer. In 1917, Vito lives in Little Italy with his wife, Carmela, and their infant son, Sonny. Black Hand extortionist Don Fanucci preys on the neighborhood, costing Vito his grocery store job. His neighbor Peter Clemenza asks Vito to hide a bag of guns. As thanks, Clemenza enlists Vito's help in stealing a rug, which he gives to Carmela.

The Corleones have two more children: Fredo and Michael. Vito, Clemenza, and new partner Salvatore Tessio earn money by stealing dresses and selling them door-to-door. Fanucci threatens to report them to the police if they do not pay him off. Vito tells his partners he can convince Fanucci to take less than the $600 he has demanded. They are skeptical but go along with the plan. Vito meets Fanucci in a restaurant during the festival of San Rocco and pays him $100, which he grudgingly accepts. Vito tracks him back to his apartment and kills him in the din of the festival. In the ensuing years, Vito gains a reputation as a defender of the neighborhood's downtrodden.

In 1922, Vito and his family travel to Sicily to establish an olive oil importing business. He and his business partner, Don Tommasino, visit Don Ciccio, ostensibly to ask for Ciccio's blessing for their business. Vito reveals his identity to the elderly and feeble Ciccio, then slices his stomach, avenging the Andolini family. Ciccio's guards shoot at Vito and Tommasino as they flee, injuring Tommasino, but he and Vito escape.

Michael

[edit]In 1958, during his son's First Communion party at Lake Tahoe, Michael has a series of meetings in his role as the don of the Corleone crime family. Johnny Ola, representing Jewish Mob boss Hyman Roth, promises Michael support in taking over a casino. Corleone capo Frank Pentangeli asks for help defending his Bronx territory against the Rosato brothers, affiliates of Roth. Michael refuses, frustrating Pentangeli. Senator Pat Geary, an anti-Italian xenophobe, demands a bribe to secure the casino license. Michael refuses and counters that Geary should pay the license fee. That night, an assassination attempt at his home prompts Michael to depart suddenly after confiding in consigliere Tom Hagen that he suspects a traitor within the family.

Michael separately tells Pentangeli and Roth that he suspects the other of planning the hit, and arranges a peace meeting between Pentangeli and the Rosatos. At the meeting the brothers attempt to strangle Pentangeli, telling him "Michael Corleone says hello!" A police officer coincidentally walks in forcing the brothers to flee. Hagen blackmails Geary into cooperating with the Corleones by having him framed for the death of a prostitute.

A sickly Roth, Michael, and several of their partners travel to Havana to discuss their Cuban business prospects under the government of Fulgencio Batista. Roth is exuberant, but Michael has doubts about the government's response to the Cuban Revolution. At a later meeting, Roth becomes angry when Michael asks who ordered the Rosatos to kill Pentangeli. On New Year's Eve Fredo pretends not to know Ola, but eventually slips, revealing himself to Michael as the traitor. Michael orders hits on Ola and Roth; his enforcer strangles Ola but is killed by Cuban soldiers as he tries to smother Roth. Batista resigns and flees Cuba due to rebel advances. During the ensuing chaos, Michael, Fredo, and Roth separately escape Cuba. Back home, Michael is told that his wife Kay has miscarried.

In Washington, D.C., a Senate committee on organized crime is investigating the Corleone family, but Geary defends them. Pentangeli agrees to testify against Michael and is placed under witness protection. On returning to Nevada, Fredo tells Michael that Ola offered him a position of responsibility and that he did not realize Roth was planning a hit. Michael disowns Fredo but orders that he should not be harmed while their mother is alive. Michael sends for Pentangeli's brother from Sicily, and Pentangeli, after seeing his brother in the hearing room, retracts his statement implicating Michael in organized crime; the hearing dissolves in an uproar. Kay reveals to Michael that she had an abortion, not a miscarriage, and that she intends to leave him and take their children. Outraged, Michael strikes Kay, banishes her from the family, and takes sole custody of the children.

Carmela dies some time later, and Michael hurries to wrap up loose ends. At the funeral, he embraces Fredo while giving a stern glance to family enforcer Al Neri. Kay visits her children; as she is saying goodbye, Michael arrives and closes the door on her. Roth returns to the United States after being refused asylum and entry to Israel. Corleone caporegime Rocco Lampone assassinates him at the airport and is shot while fleeing. Hagen visits Pentangeli at the army barracks where he is being held and the two discuss how failed conspirators against a Roman emperor could save their families by committing suicide. Pentangeli is later found dead in his bathtub, having slit his wrists. Neri takes Fredo fishing and shoots him as Michael watches from the compound.

Michael reminisces about Vito's 50th birthday party on December 7, 1941, the same day Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. While the family waits to surprise Vito, Michael announces that he dropped out of college and joined the Marines, angering Sonny and surprising Hagen. Fredo is the only member of the family who supports his decision. Vito arrives and everyone but Michael goes to welcome him.

In the present day, Michael sits alone at the family compound looking out over the lake.

Cast

[edit]- Al Pacino as Michael Corleone

- Robert Duvall as Tom Hagen

- Diane Keaton as Kay Adams Corleone

- Robert De Niro as Vito Corleone

- Oreste Baldini as young Vito Corleone

- John Cazale as Fredo Corleone

- Talia Shire as Connie Corleone

- Lee Strasberg as Hyman Roth

- Michael V. Gazzo as Frank Pentangeli

- G. D. Spradlin as Senator Pat Geary

- Richard Bright as Al Neri

- Gastone Moschin as Don Fanucci

- Tom Rosqui as Rocco Lampone

- Bruno Kirby as young Peter Clemenza

- Frank Sivero as Genco Abbandando

- Morgana King as Mama Carmela Corleone

- Francesca De Sapio as young Carmela Corleone

- Marianna Hill as Deanna Corleone

- Leopoldo Trieste as Signor Roberto

- Dominic Chianese as Johnny Ola

- Amerigo Tot as Bussetta, Michael's Sicilian bodyguard

- Troy Donahue as Merle Johnson[N 2]

- Joe Spinell as Willi Cicci

- Abe Vigoda as Salvatore Tessio

- John Aprea as young Tessio

- Harry Dean Stanton as an F.B.I. agent

- Carmine Caridi as Carmine Rosato

- Danny Aiello as Tony Rosato

- James Caan as Sonny Corleone

- Gianni Russo as Carlo Rizzi

- Roger Corman as Senator #2

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]

Mario Puzo started writing a script for a sequel in December 1971, before The Godfather was even released; its initial title was The Death of Michael Corleone.[7] Francis Ford Coppola's idea for the sequel would be to "juxtapose the ascension of the family under Vito Corleone with the decline of the family under his son Michael ... I had always wanted to write a screenplay that told the story of a father and a son at the same age. They were both in their thirties and I would integrate the two stories ... In order not to merely make Godfather I over again, I gave Godfather II this double structure by extending the story in both the past and in the present".[8] Coppola met with Martin Scorsese about directing the film, but Paramount refused.[9][10][11][12] Coppola also, in his director's commentary on The Godfather Part II, mentioned that the scenes depicting the Senate committee interrogation of Michael Corleone and Frank Pentangeli are based on the Joseph Valachi federal hearings and that Pentangeli is a Valachi-like figure.[13]

Production, however, nearly ended before it began when Pacino's lawyers told Coppola that he had grave misgivings with the script and was not coming. Coppola spent an entire night rewriting it before giving it to Pacino for his review. Pacino approved it and the production went forward.[14] The film's original budget was $6 million but costs increased to over $11 million, with Variety's review claiming it was over $15 million.[15]

Casting

[edit]

Several actors from the first film did not return for the sequel. Marlon Brando initially agreed to return for the birthday flashback sequence, but the actor, feeling mistreated by the board at Paramount, failed to show up for the single day's shooting.[16] Coppola then rewrote the scene that same day.[16] Richard S. Castellano, who portrayed Peter Clemenza in the first film, also declined to return, as he and the producers could not reach an agreement on his demands that he be allowed to write the character's dialogue in the film, though this claim was disputed by Castellano's widow in a 1991 letter to People magazine.[17] The part in the plot originally intended for the latter-day Clemenza was then filled by the character of Frank Pentangeli, played by Michael V. Gazzo.[18]

Coppola offered James Cagney a part in the film, but he refused.[19] James Caan agreed to reprise the role of Sonny in the birthday flashback sequence, demanding he be paid the same amount he received for the entire previous film for the single scene in Part II, which he received.[16] Among the actors depicting Senators in the hearing committee are film producer/director Roger Corman, writer/producer William Bowers, producer Phil Feldman, and actor Peter Donat.[20]

Filming

[edit]The Godfather Part II was shot between October 1, 1973, and June 19, 1974. The scenes that took place in Cuba were shot in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic.[21] Charles Bluhdorn, whose Gulf+Western conglomerate owned Paramount, felt strongly about developing the Dominican Republic as a movie-making site. Forza d'Agrò was the Sicilian town featured in the film.[22]

Unlike with the first film, Coppola was given near-complete control over production. In his commentary, he said this resulted in a shoot that ran very smoothly despite multiple locations and two narratives running parallel within one film.[14] Coppola discusses his decision to make this the first major U.S. motion picture to use "Part II" in its title in the director's commentary on the DVD edition of the film released in 2002.[14] Paramount was initially opposed because they believed the audience would not be interested in an addition to a story they had already seen. But the director prevailed, and the film's success began the common practice of numbered sequels.

Only three weeks prior to the release, film critics and journalists pronounced Part II a disaster. The cross-cutting between Vito and Michael's parallel stories were judged too frequent, not allowing enough time to leave a lasting impression on the audience. Coppola and the editors returned to the cutting room to change the film's narrative structure, but could not complete the work in time, leaving the final scenes poorly timed at the opening.[23]

It was the last major American motion picture to have release prints made with Technicolor's dye imbibition process until the late 1990s.

Music

[edit]Release

[edit]Theatrical

[edit]The Godfather Part II premiered in New York City on December 12, 1974, and was released in the United States on December 20, 1974.

Home media

[edit]Coppola created The Godfather Saga expressly for American television in a 1975 release that combined The Godfather and The Godfather Part II with unused footage from those two films in a chronological telling that toned down the violent, sexual, and profane material for its NBC debut on November 18, 1977. In 1981, Paramount released the Godfather Epic VHS box set, which also told the story of the first two films in chronological order, again with additional scenes, but not redacted for broadcast sensibilities. Coppola returned to the film again in 1992 when he updated that release with footage from The Godfather Part III and more unreleased material. This home viewing release, under the title The Godfather Trilogy 1901–1980, had a total run time of 583 minutes (9 hours, 43 minutes), not including the set's bonus documentary by Jeff Werner on the making of the films, "The Godfather Family: A Look Inside".

The Godfather DVD Collection was released on October 9, 2001, in a package[24] that contained all three films—each with a commentary track by Coppola—and a bonus disc that featured a 73-minute documentary from 1991 entitled The Godfather Family: A Look Inside and other miscellany about the film: the additional scenes originally contained in The Godfather Saga; Francis Coppola's Notebook (a look inside a notebook the director kept with him at all times during the production of the film); rehearsal footage; a promotional featurette from 1971; and video segments on Gordon Willis's cinematography, Nino Rota's and Carmine Coppola's music, the director, the locations and Mario Puzo's screenplays. The DVD also held a Corleone family tree, a "Godfather" timeline, and footage of the Academy Award acceptance speeches.[25]

The restoration was confirmed by Francis Ford Coppola during a question-and-answer session for The Godfather Part III, when he said that he had just seen the new transfer and it was "terrific".

Restoration

[edit]After a careful restoration by Robert A. Harris of Film Preserve, the first two Godfather films were released on DVD and Blu-ray on September 23, 2008, under the title The Godfather: The Coppola Restoration. The Blu-ray Disc box set (four discs) includes high-definition extra features on the restoration and film. They are included on Disc 5 of the DVD box set (five discs).

Other extras are ported over from Paramount's 2001 DVD release. There are slight differences between the repurposed extras on the DVD and Blu-ray Disc sets, with the HD box having more content.[26]

Paramount Pictures restored and remastered The Godfather, The Godfather Part II, and The Godfather Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone (a re-edited cut of the third film) for a limited theatrical run and home media release on Blu-ray and 4K Blu-ray to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the premiere of The Godfather. The disc editions were released on March 22, 2022.[27]

Video game

[edit]A video game based on the film was released for Windows, PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 in April 2009 by Electronic Arts. It received mixed or average reviews and sold poorly, leading Electronic Arts to cancel plans for a game based on The Godfather Part III.[28]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Although The Godfather Part II did not surpass the original film commercially, it grossed $47.5 million in the United States and Canada.[2] and was Paramount Pictures' highest-grossing film of 1974, and the seventh-highest-grossing picture in the United States. According to its international distributor, the film had grossed $45.3 million internationally by 1994,[29] for a worldwide total of $93 million.[N 1]

Critical response

[edit]Initial critical reception of The Godfather Part II was divisive,[33] with some dismissing the work and others declaring it superior to the first film.[34][35] Pauline Kael in The New Yorker was an early champion, writing that the film was visually "far more complexly beautiful than the first, just as it's thematically richer, more shadowed, more full."[36] However, while the film's cinematography and acting were immediately acclaimed, many criticized it as overly slow-paced and convoluted.[37] Vincent Canby of The New York Times viewed the film as "stitched together from leftover parts. It talks. It moves in fits and starts but it has no mind of its own ... The plot defies any rational synopsis."[18] Stanley Kauffmann of The New Republic cited what he called "gaps and distentions" in the story.[38] William Pechter of Commentary, while admiring the movie, regretted what he saw as its archness and self-importance, calling it an "overly deliberate and self-conscious attempt to make a film that's unmistakably a serious work of art," and professing to "know of no one except movie critics who likes Part II as much as part one."[39]

A mildly positive Roger Ebert awarded three out of four[40] and wrote that the flashbacks "give Coppola the greatest difficulty in maintaining his pace and narrative force. The story of Michael, told chronologically and without the other material, would have had really substantial impact, but Coppola prevents our complete involvement by breaking the tension." Though praising Pacino's performance and lauding Coppola as "a master of mood, atmosphere, and period", Ebert considered the chronological shifts of its narrative "a structural weakness from which the film never recovers".[37] Gene Siskel gave the film three-and-a-half out of four, writing that it was at times "as beautiful, as harrowing, and as exciting as the original. In fact, The Godfather, Part II may be the second best gangster movie ever made. But it's not the same. Sequels can never be the same. It's like being forced to go to a funeral the second time—the tears just don't flow as easily."[41]

Critical re-assessment

[edit]The film quickly became the subject of a critical re-evaluation.[42] Whether considered separately or with its predecessor as one work, The Godfather Part II is now widely regarded as one of the greatest films in world cinema. Many critics compare it favorably with the original – although it is rarely ranked higher on lists of "greatest" films. On Rotten Tomatoes, it holds a 96% approval rating based on 126 reviews, with an average rating of 9.7/10. The consensus reads, "Drawing on strong performances by Al Pacino and Robert De Niro, Francis Ford Coppola's continuation of Mario Puzo's Mafia saga set new standards for sequels that have yet to be matched or broken."[43] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 90 out of 100 based on 18 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[44]

Michael Sragow's conclusion in his 2002 essay, selected for the National Film Registry web site, is that "[a]lthough The Godfather and The Godfather Part II depict an American family's moral defeat, as a mammoth, pioneering work of art it remains a national creative triumph."[45] In his 2014 review of the film, Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian wrote "Francis Coppola's breathtakingly ambitious prequel-sequel to his first Godfather movie is as gripping as ever. It is even better than the first film, and has the greatest single final scene in Hollywood history, a real coup de cinéma."[46]

The Godfather Part II was featured on Sight & Sound's Director's list of the ten greatest films of all time in 1992 (ranked at No. 9)[47] and 2002 (where it was ranked at No. 2. The critics ranked it at No. 4)[48][49][50] On the 2012 list by the same magazine the film was ranked at No. 31 by critics and at No. 30 by directors.[51][52][53] In 2006, Writers Guild of America ranked the film's screenplay (Written by Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppla) the 10th greatest ever.[54] It ranked No. 7 on Entertainment Weekly's list of the "100 Greatest Movies of All Time", and #1 on TV Guide's 1999 list of the "50 Greatest Movies of All Time on TV and Video".[55] The Village Voice ranked The Godfather Part II at No. 31 in its Top 250 "Best Films of the Century" list in 1999, based on a poll of critics.[56] In January 2002, the film (along with The Godfather) made the list of the "Top 100 Essential Films of All Time" by the National Society of Film Critics.[57][58] In 2017, it ranked No. 12 on Empire magazine's reader's poll of The 100 Greatest Movies.[59] In an earlier poll held by the same magazine in 2008, it was voted 19th on the list of 'The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time'.[60] In 2015, it was tenth in the BBC's list of the 100 greatest American films.[61]

Many believe Pacino's performance in The Godfather Part II is his finest acting work. It is now regarded as one of the greatest performances in film history. In 2006, Premiere issued its list of "The 100 Greatest Performances of all Time", putting Pacino's performance at #20.[62] Later in 2009, Total Film issued "The 150 Greatest Performances of All Time", ranking Pacino's performance fourth place.[63]

The Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa cited it as one of his 100 favorite films.[64]

Ebert added the film to his Great Movies canon, noting he "would not change a word" of his original review but praising the work as "grippingly written, directed with confidence and artistry, photographed by Gordon Willis ... in rich, warm tones." He praises the score: "More than ever, I am convinced it is instrumental to the power and emotional effect of the films. I cannot imagine them without their Nino Rota scores. Against all our objective reason, they instruct us how to feel about the films. Now listen very carefully to the first notes as the big car drives into Miami. You will hear an evocative echo of Bernard Hermann’s score for Citizen Kane, another film about a man who got everything he wanted and then lost it." [65]

Accolades

[edit]This film is the first sequel to win the Academy Award for Best Picture.[66] The Godfather and The Godfather Part II remain the only original/sequel combination both to win Best Picture.[67] Along with The Lord of the Rings, The Godfather Trilogy shares the distinction that all of its installments were nominated for Best Picture; additionally, The Godfather Part II and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King are so far the only sequels to win Best Picture. Al Pacino became the fourth actor to be Oscar-nominated twice for playing the same character.

American Film Institute recognition

[edit]- 1998: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies – #32[68]

- 2003: AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains:

- Michael Corleone – #11 Villain[69]

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- "Keep your friends close, but your enemies closer." – #58[70]

- "I know it was you, Fredo. You broke my heart. You broke my heart." – Nominated[71]

- "Michael, we're bigger than U.S. Steel." – Nominated[71]

- 2007: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – #32[72]

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10 – #3 Gangster Film and Nominated Epic Film[73]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Godfather II to intermission. 3hrs 42 minutes total". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on July 17, 2015. Retrieved December 20, 2014.

- ^ a b "The Godfather Part II (1974)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- ^ "The Godfather: Part II (1974) – Financial Information". The Numbers. Archived from the original on April 6, 2015. Retrieved December 20, 2014.

- ^ Stax (July 28, 2003). "Featured Filmmaker: Francis Ford Coppola". Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ^ "Citizen Kane Stands the Test of Time" Archived August 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. American Film Institute.

- ^ "The National Film Registry List – Library of Congress". loc.gov. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2012.

- ^ "The Godfather". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. April 28, 2015. Archived from the original on March 31, 2020. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- ^ Phillips, Gene (2004). Godfather: The Intimate Francis Ford Coppola. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2304-2.

- ^ Morris, Andy (September 24, 2012). "'The Godfather Part IV'". GQ. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (December 12, 2014). "'The Godfather Part II' at 40". Time. Archived from the original on November 20, 2022. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Barfield, Charles (May 13, 2019). "Francis Ford Coppola Explains How 'Patton' Saved His 'Godfather' Job & Why He Wanted Martin Scorsese To Helm The Sequel". The Playlist. Archived from the original on November 20, 2022. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (May 16, 2023). "Martin Scorsese, Leonardo DiCaprio & Robert De Niro On How They Found The Emotional Handle For Their Cannes Epic 'Killers Of The Flower Moon'". Deadline. Archived from the original on May 20, 2023. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ "Director commentary". The Godfather Part II. 1974. ASIN B00003CXAA.

- ^ a b c The Godfather Part II DVD commentary featuring Francis Ford Coppola, [2005]

- ^ The Godfather Part II at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- ^ a b c Jagernauth, Kevin (April 9, 2012). "5 Things You May Not Know About the 'The Godfather Part II'". IndieWire. Archived from the original on October 10, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ Sheridan-Castellano, Ardell (2003). Divine Intervention and a Dash of Magic... Unraveling The Mystery of "The Method" + Behind the Scenes of the Original Godfather Film. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 1-55369-866-5.

- ^ a b Canby, Vincent (December 13, 1974). "'Godfather, Part II' Is Hard To Define: The Cast". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Cagney, James (1976). Cagney by Cagney. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-671-80889-1. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ Eagan, Daniel (2010). America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. New York: Continuum. p. 711. ISBN 978-0-8264-2977-3.

- ^ "Movie Set Hotel: The Godfather II Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine", HotelChatter, May 12, 2006.

- ^ "In search of... The Godfather in Sicily". The Independent. Independent Digital News and Media Limited. April 26, 2003. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- ^ The Godfather Family: A look Inside

- ^ "DVD review: 'The Godfather Collection'". DVD Spin Doctor. July 2007.

- ^ The Godfather DVD Collection [2001]

- ^ "Godfather: Coppola Restoration", September 23 Archived January 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine on DVD Spin Doctor

- ^ "'The Godfather Trilogy Releasing to 4k, Finally". January 13, 2022. Archived from the original on November 25, 2022. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ "EA buries Godfather franchise". GameSpot. June 9, 2009. Archived from the original on July 26, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ^ "UIP's $25M-Plus Club". Variety. September 11, 1995. p. 92.

- ^ "The Godfather: Part II (1974)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

Original release: $47,643,435; 2010 re-release: $85,768; 2019 re-release: $291,754

- ^ Thompson, Anne (December 24, 1990). "Is 'Godfather III' an offer audiences cannot refuse?". Variety. p. 57.

- ^ "'The Godfather Part II' At 45 And Why It Remains The Gold Standard For Sequels". forbes.com. November 9, 2019. Archived from the original on December 17, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Eagan, Daniel (2009). America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 712. ISBN 978-1-4411-1647-5.

- ^ Biskind, Peter (1991). The Godfather Companion. Wildside Press. ISBN 0-8095-9036-0.

- ^ "The Godfather, Part II". Turner Classic Movies, Inc. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Pauline Kael (December 23, 1974). "Fathers and Sons". The New Yorker.

- ^ a b "The 'Godfather Part II' Sequel Syndrome". Newsweek. December 25, 2016. Archived from the original on March 7, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

But when the movie arrived in theaters at the end of 1974, it was met with a critical reception that, compared with today's exuberant embrace, felt more like a slap in the face ... Most professional tastemakers, even those exasperated by what they felt was the movie's sometimes plodding-pace, recognized the creative crowning achievements of the film's direction, cinematography and acting.

- ^ Berliner, Todd (2010). Hollywood Incoherent: Narration in Seventies Cinema. University of Texas Press. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0-292-72279-8. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "Pechter, William, "Godfather II," Commentary, March 1975". March 1975. Archived from the original on July 2, 2023. Retrieved July 2, 2023.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "The Godfather, Part II". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on December 8, 2017. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (December 20, 1974). "'The Godfather, Part II': Father knew best". Chicago Tribune. No. 3. p. 1.

- ^ Garner, Joe (2013). Now Showing: Unforgettable Moments from the Movies. Andrews McMeel Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4494-5009-0. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "The Godfather, Part II". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on May 12, 2019. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ "The Godfather: Part II (1974)". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on August 12, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ Sragow, Michael (2002). "The Godfather and The Godfather Part II" (PDF). "The A List: The National Society of Film Critics' 100 Essential Films," 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 24, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (February 20, 2014). "The Godfather: Part II – review". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 30, 2022. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- ^ "The Sight & Sound Top Ten Poll 1992". thependragonsociety. September 24, 2017. Archived from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ "Sight & Sound 2002 Directors' Greatest Films poll". listal.com. Archived from the original on May 15, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ "Sight & Sound Top Ten Poll 2002 – The Critics' Top Ten Films". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ "Sight & Sound Top Ten Poll 2002 – The Directors' Top Ten Films". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ "Directors' Top 100". Sight & Sound. British Film Institute. 2012. Archived from the original on February 9, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ "Critics' Top 100". Sight & Sound. British Film Institute. 2012. Archived from the original on February 7, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Films of All Time". Sight & Sound. BFI. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ "101 Greatest Screenplays". Writers Guild of America. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "TV Guide's 50 Greatest Movies On TV/Video". thependragon.co.uk. Archived from the original on November 4, 2015. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ^ "Take One: The First Annual Village Voice Film Critics' Poll". The Village Voice. 1999. Archived from the original on August 26, 2007. Retrieved July 27, 2006.

- ^ Carr, Jay (2002). The A List: The National Society of Film Critics' 100 Essential Films. Da Capo Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-306-81096-1. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ^ "100 Essential Films by The National Society of Film Critics". filmsite.org. Archived from the original on July 16, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Movies". Archived from the original on July 6, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Green, Willow (October 3, 2008). "The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire. Archived from the original on November 6, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest American Films". bbc. July 20, 2015. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Performances" Archived August 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine filmsite.org

- ^ "The 150 Greatest Performances Of All Time" Archived January 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine TotalFilm. com

- ^ Thomas-Mason, Lee (January 12, 2021). "From Stanley Kubrick to Martin Scorsese: Akira Kurosawa once named his top 100 favourite films of all time". Far Out Magazine. Archived from the original on April 2, 2023. Retrieved January 23, 2023.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (October 2, 2008). ""This is the business we've chosen" (1974)". Archived from the original on May 9, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ a b "47th Academy Awards Winners: Best Picture". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. October 6, 2014. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ McNamara, Mary (December 2, 2010). "Critic's Notebook: Can 'Harry Potter' ever capture Oscar magic?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Heroes & Villains" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 28, 2014. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movie Quotes" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 13, 2011. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ a b "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movie Quotes Nominees" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 6, 2013. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10: Top 10 Gangster". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on November 18, 2016. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

External links

[edit]- The Godfather Part II at IMDb

- The Godfather Part II at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- The Godfather Part II at Box Office Mojo

- The Godfather Part II at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Godfather Part II at Metacritic

- The Godfather and The Godfather Part II essay by Michael Sragow on the National Film Registry website. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- 1974 films

- The Godfather films

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s American films

- 1974 crime films

- American crime films

- American crime drama films

- American epic films

- American prequel films

- American sequel films

- BAFTA winners (films)

- Best Picture Academy Award winners

- Crimes against sex workers in fiction

- Cultural depictions of the Mafia

- Films about brothers

- Films about father–son relationships

- Films about the American Mafia

- Films about the Cuban Revolution

- Films about the Sicilian Mafia

- Films based on American crime novels

- Films based on organized crime novels

- Films directed by Francis Ford Coppola

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award-winning performance

- Films produced by Francis Ford Coppola

- Films scored by Nino Rota

- Films set in 1901

- Films set in 1917

- Films set in 1922

- Films set in 1941

- Films set in 1958

- Films set in 1959

- Films set in the 1900s

- Films set in the 1910s

- Films set in the 1920s

- Films set in the 1940s

- Films set in the 1950s

- Films set in the United States

- Films set in Italy

- Films set in Cuba

- Films set in Florida

- Films set in New York (state)

- Films set in Nevada

- Films set in Havana

- Films set in New York City

- Films set in Sicily

- Films set in the Las Vegas Valley

- Films set in Miami

- Films shot in Miami

- Films shot in New York City

- Films shot in the Las Vegas Valley

- Films that won the Best Original Score Academy Award

- Films whose art director won the Best Art Direction Academy Award

- Films whose director won the Best Directing Academy Award

- Films whose writer won the Best Adapted Screenplay Academy Award

- Films with screenplays by Francis Ford Coppola

- Films with screenplays by Mario Puzo

- Fiction about fratricide

- Paramount Pictures films

- Saturn Award–winning films

- Sicilian-language films

- United States National Film Registry films

- Films set in Queens, New York

- Films about siblicide

- English-language crime films