History of archaeology

Archaeology is the study of human activity in the past, primarily through the recovery and analysis of the material culture and environmental data that they have left behind, which includes artifacts, architecture, biofacts (also known as eco-facts) and cultural landscapes (the archaeological record).

The development of the field of archaeology has its roots with history and with those who were interested in the past, such as kings and queens who wanted to show past glories of their respective nations. In the 6th century BCE, Nabonidus of the Neo-Babylonian Empire excavated, surveyed and restored sites built more than a millennium earlier under Naram-sin of Akkad. The 5th-century-BCE Greek historian Herodotus was the first scholar to systematically study the past and also an early examiner of artifacts. In Medieval India, the study of the past was recorded. In the Song Empire (960–1279) of imperial China, Chinese scholar-officials unearthed, studied, and cataloged ancient artifacts, a native practice that continued into the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) before adoption of Western methods. The 15th and 16th centuries saw the rise of antiquarians in Renaissance Europe such as Flavio Biondo who were interested in the collection of artifacts. The antiquarian movement shifted into nationalism as personal collections turned into national museums. It evolved into a much more systematic discipline in the late 19th century and became a widely used tool for historical and anthropological research in the 20th century. During this time there were also significant advances in the technology used in the field.

The OED first cites "archaeologist" from 1824; this soon took over as the usual term for one major branch of antiquarian activity. "Archaeology", from 1607 onwards, initially meant what we would call "ancient history" generally, with the narrower modern sense first seen in 1837.

Beginnings

[edit]Khaemweset, a son of ancient Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses II, was known for his keen interest in identifying and restoring monuments of Egypt's past, such as Djoser's step pyramid. This pyramid, having been built in the 27th century BCE, predated Khaemweset by approximately 1,400 years. Due to his activities, he is sometimes nicknamed "the first Egyptologist".

In ancient Mesopotamia, a foundation deposit of the Akkadian Empire ruler Naram-Sin (ruled c. 2200 BCE) was discovered and analysed by king Nabonidus of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, c. 550 BCE, who is thus known as the first archaeologist.[1][2][3] Not only did he lead the first excavations which were to find the foundation deposits of the temples of Šamaš the sun god, the warrior goddess Anunitu (both located in Sippar), and the sanctuary that Naram-Sin built to the moon god, located in Harran, but he also had them restored to their former glory.[1] He was also the first to date an archaeological artifact in his attempt to date Naram-Sin's temple during his search for it.[4] Even though his estimate was inaccurate by about 1,500 years, it was still a very good one considering the lack of accurate dating technology.[1][4][2]

Early systemic investigation and historiography can be traced back to the Greek historian Herodotus (c. 484 – c. 425 BCE). He was the first western scholar to systematically collect artifacts and test their accuracy. He was also the first to make a compelling narrative of the past. He is known for a set of nine books called the Histories, in which he wrote everything he could learn about different regions. He discussed the causes and consequences of the Greco-Persian Wars. He also explored the Nile and Delphi. However, scholars[who?] have found errors in his records and believe he probably did not go as far up the Nile as he claimed.

Antiquarians

[edit]

Archaeology later concerned itself with the antiquarianism movement. Antiquarians studied history with particular attention to ancient artifacts and manuscripts, as well as historical sites. They usually were wealthy people. They collected artifacts and displayed them in cabinets of curios. Antiquarianism also focused on the empirical evidence that existed for the understanding of the past, encapsulated in the motto of the 18th-century antiquary Sir Richard Colt Hoare, "We speak from facts not theory". Tentative steps towards the systematization of archaeology as a science took place during the Enlightenment era in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries.[5]

Imperial China

[edit]During the Song dynasty (960–1279) in China, educated gentry became interested in the antiquarian pursuit of art collecting.[6] Neo-Confucian scholar-officials were generally concerned with archaeological pursuits in order to revive the use of ancient Shang, Zhou, and Han relics in state rituals.[7] This attitude was criticized by the polymath official Shen Kuo (1031–1095) in his Dream Pool Essays of 1088. He endorsed the idea that materials, technologies, and objects of antiquity should be studied for their functionality and for the discovery of ancient manufacturing techniques.[7] Although a distinct minority, there were others who took the discipline as seriously as Shen did. For instance, the official, historian, poet, and essayist Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072) compiled an analytical catalogue of ancient rubbings on stone and bronze.[8][9] Zhao Mingcheng (1081–1129) stressed the importance of using ancient inscriptions to correct discrepancies and errors in later historical texts discussing ancient events.[9][10] Native Chinese antiquarian studies waned during the Yuan (1279–1368) and Ming (1368–1644) dynasties, were revived during the Qing dynasty (1644–1912), but never developed into a systematic discipline of archaeology outside of Chinese historiography.[11][12] The Chong xiu Xuanhe bogutu (重修宣和博古圖) archaeological collection catalogue commissioned by Emperor Huizong of Song (r. 1100–1125) was widely reprinted in the 16th century during the Ming period,[13] but it was criticized by Hong Mai (1123–1202) for containing inaccuracies about Han dynasty artifacts.[14]

Medieval India

[edit]The 12th century Indian scholar Kalhana's writings involved recording of local traditions, examining manuscripts, inscriptions, coins and architectures, which is described as one of the earliest traces of archaeology. One of his notable work is called Rajatarangini which was completed in c.1150 and is described as one of the first history books of India.[15][16][17]

Renaissance Europe

[edit]

In Europe, interest in the remains of Greco-Roman civilisation and the rediscovery of classical culture began in the Late Middle Ages. Despite the importance of antiquarian writing in the literature of ancient Rome, such as Livy's discussion of ancient monuments,[18] scholars generally view antiquarianism as emerging only in the Middle Ages.[19] Flavio Biondo, an Italian Renaissance humanist historian, created a systematic guide to the ruins and topography of ancient Rome in the early 15th century, for which he has been called an early founder of archaeology.[20][21] The itinerant scholar Ciriaco de' Pizzicolli or Cyriacus of Ancona (1391–c. 1455) also traveled throughout Greece to record his findings on ancient buildings and objects. Ciriaco traveled all around the Eastern Mediterranean, noting his archaeological discoveries in a day-book, Commentaria, that eventually filled six volumes. He has been called the "father of archaeology" by historians such as Edward W. Bodnar:

Cyriac of Ancona was the most enterprising and prolific recorder of Greek and Roman antiquities, particularly inscriptions, in the fifteenth century, and the general accuracy of his records entitles him to be called the founding father of modern classical archeology.[22]

English antiquarians of the 16th century including John Leland and William Camden conducted topographical surveys of England's countryside, drawing, describing and interpreting the monuments that they encountered.[23][24] These individuals were frequently clergymen: many vicars recorded local landmarks within their parishes, details of the landscape and ancient monuments such as standing stones—even if they did not always understand the significance of what they were seeing.

Shift to nationalism

[edit]In the late 18th to 19th century archaeology became a national endeavor as personal cabinets of curios turned into national museums. People were now being hired to go out and collect artifacts to make a nation's collection more grand and to show how far a nation's reach extends. For example, Giovanni Battista Belzoni was hired by Henry Salt, the British consul to Egypt, to gather antiquities for Britain. In nineteenth-century Mexico, the expansion of the National Museum of Anthropology and the excavation of major archaeological ruins by Leopoldo Batres were part of the liberal regime of Porfirio Díaz to create a glorious image of Mexico's pre-Hispanic past.[25]

First excavations

[edit]

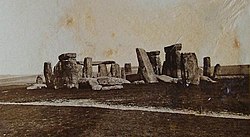

Among the first sites to undergo archaeological excavation were Stonehenge and other megalithic monuments in England. The first known excavations made at Stonehenge were conducted by William Harvey and Gilbert North in the early 17th century. Both Inigo Jones and the Duke of Buckingham also dug there shortly afterwards. John Aubrey was a pioneer archaeologist who recorded numerous megalithic and other field monuments in southern England. He also mapped the Avebury henge monument. He wrote Monumenta Britannica in the late 17th century as a survey of early urban and military sites, including Roman towns, "camps" (hillforts), and castles, and a review of archaeological remains, including sepulchral monuments, roads, coins and urns. He was also ahead of his time in the analysis of his findings. He attempted to chart the chronological stylistic evolution of handwriting, medieval architecture, costume, and shield shapes.[26]

William Stukeley was another antiquarian who contributed to the early development of archaeology in the early 18th century. He also investigated the prehistoric monuments of Stonehenge and Avebury, work for which he has been remembered as "probably... the most important of the early forerunners of the discipline of archaeology".[27] He was one of the first to attempt to date the megaliths, arguing that they were a remnant of the pre-Roman druidic religion.

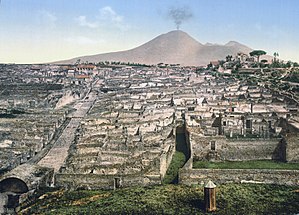

Excavations were carried out in the ancient towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum, both of which had been covered by ashes during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in the year 79. These excavations began in 1748 in Pompeii, while in Herculaneum they began in 1738 under the auspices of King Charles VII of Naples. In Herculaneum, the Theatre, the Basilica and the Villa of the Papyri were discovered in 1768. The discovery of entire towns, complete with utensils and even human shapes, as well the unearthing of ancient frescos, had much impact throughout Europe.

A very influential figure in the development of the theoretical and systematic study of the past through its physical remains was "the prophet and founding hero of modern archaeology," Johann Joachim Winckelmann.[28] Winckelmann was a founder of scientific archaeology by first applying empirical categories of style on a large, systematic basis to the classical (Greek and Roman) history of art and architecture. His original approach was based on detailed empirical examinations of artefacts from which reasoned conclusions could be drawn and theories developed about ancient societies.

In America, Thomas Jefferson, possibly inspired by his experiences in Europe, supervised the systematic excavation of a Native American burial mound on his land in Virginia in 1784. Although Jefferson's investigative methods were ahead of his time, they were primitive by today's standards.

Napoleon's army carried out excavations during its Egyptian campaign, in 1798–1801, which also was the first major overseas archaeological expedition. The emperor took with him a force of 500 civilian scientists, specialists in fields such as biology, chemistry and languages, in order to carry out a full study of the ancient civilisation. The work of Jean-François Champollion in deciphering the Rosetta Stone to discover the hidden meaning of hieroglyphics proved the key to the study of Egyptology.[29]

However, prior to the development of modern techniques excavations tended to be haphazard; the importance of concepts such as stratification and context were completely overlooked. For instance, in 1803, there was widespread criticism of Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin for removing the Elgin Marbles from the Parthenon in Athens. The marble sculptures themselves, however, were valued by his critics only for their aesthetic qualities, not for the information they contained about Ancient Greek civilization.[30]

In the first half of the 19th century many other archaeological expeditions were organized; Giovanni Battista Belzoni and Henry Salt collected Ancient Egyptian artifacts for the British Museum, Paul Émile Botta excavated the palace of Assyrian ruler Sargon II, Austen Henry Layard unearthed the ruins of Babylon and Nimrud and discovered the Library of Ashurbanipal and Robert Koldeway and Karl Richard Lepsius excavated sites in the Middle East. However, the methodology was still poor, and the digging was aimed at the discovery of artefacts and monuments.

Development of archaeological method

[edit]

The father of archaeological excavation was William Cunnington (1754–1810). He undertook excavations in Wiltshire from around 1798, in collaboration with his regular excavators Stephen and John Parker of Heytesbury.[31] Cunnington's work was funded by a number of patrons, the wealthiest of whom was Richard Colt Hoare, who had inherited the Stourhead estate from his grandfather in 1785. Hoare turned his attention to antiquarian pursuits and began funding Cunnington's excavations in 1804. The latter's site reports and descriptions were published by Hoare in a book entitled Ancient Historie of Wiltshire in 1810, a copy of which is kept at Stourhead.

Cunnington made meticulous recordings of mainly neolithic and Bronze Age barrows, and the terms he used to categorise and describe them are still used by archaeologists today. The first reference to the use of a trowel on an archaeological site was made in a letter from Cunnington to Hoare in 1808, which describes John Parker using one in the excavation of Bush Barrow.[32]

One of the major achievements of 19th century archaeology was the development of stratigraphy. The idea of overlapping strata tracing back to successive periods was borrowed from the new geological and palaeontological work of scholars like William Smith, James Hutton and Charles Lyell. The application of stratigraphy to archaeology first took place with the excavations of prehistorical and Bronze Age sites. In the third and fourth decade of the 19th century, archaeologists like Jacques Boucher de Perthes and Christian Jürgensen Thomsen began to put the artifacts they had found in chronological order.

Another important development was the idea of deep time. Before this, people had the notion that the earth was quite young. James Ussher used the Old Testament and calculated that the origins of the world were on 23 October 4004 BCE (a Sunday). Later Jacques Boucher de Perthes (1788–1868) established a much deeper sense of time in Antiquités celtiques et antédiluviennes (1847).

Professionalisation

[edit]As late as the mid-19th century, archaeology was still regarded as an amateur pastime by scholars. Britain's large colonial empire provided a great opportunity for such 'amateurs' to unearth and study the antiquities of many other cultures. A major figure in the development of archaeology into a rigorous science was the army officer and ethnologist, Augustus Pitt Rivers.[33]

In 1880, he began excavations on lands that came to him in inheritance and which contained a wealth of archaeological material from the Roman and Saxon periods. He excavated these over seventeen seasons, beginning in the mid-1880s and ending with his death. His approach was highly methodical by the standards of the time, and he is widely regarded as the first scientific archaeologist. Influenced by the evolutionary writings of Charles Darwin and Herbert Spencer, he arranged the artefacts typologically and (within types) chronologically. This style of arrangement, designed to highlight the evolutionary trends in human artefacts, was a revolutionary innovation in museum design, and was of enormous significance for the accurate dating of the objects. His most important methodological innovation was his insistence that all artefacts, not just beautiful or unique ones, be collected and catalogued. This focus on everyday objects as the key to understanding the past broke decisively with past archaeological practice, which had often verged on treasure hunting.[34]

William Flinders Petrie is another man who may legitimately be called the Father of Archaeology. Petrie was the first to scientifically investigate the Great Pyramid in Egypt during the 1880s. Many hypotheses as to how the pyramids had been constructed had been proposed (such as by Charles Piazzi Smyth),[35] but Petrie's exemplary analysis of the architecture of Giza disproved these hypothesis and still provides much of the basic data regarding the pyramid plateau to this day.[36]

His painstaking recording and study of artefacts, both in Egypt and later in Palestine, laid down many of the ideas behind modern archaeological recording; he remarked that "I believe the true line of research lies in the noting and comparison of the smallest details." Petrie developed the system of dating layers based on pottery and ceramic findings, which revolutionized the chronological basis of Egyptology. He was also responsible for mentoring and training a whole generation of Egyptologists, including Howard Carter, who went on to achieve fame with the discovery of the tomb of 14th-century BCE pharaoh Tutankhamun.

The first stratigraphic excavation to reach wide popularity with the public was that of Hissarlik, on the site of ancient Troy, carried out by Heinrich Schliemann, Frank Calvert, Wilhelm Dörpfeld and Carl Blegen in the 1870s. These scholars distinguished nine successive cities, from prehistory to the Hellenistic period. Their work has been criticized as rough and damaging—Kenneth W. Harl wrote that Schliemann's excavations were carried out with such rough methods that he did to Troy what the Greeks could not do in their times, destroying and levelling down the entire city walls to the ground.[37]

Meanwhile, the work of Sir Arthur Evans at Knossos in Crete revealed the ancient existence of an advanced civilisation. Many of the finds from this site were catalogued and brought to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, where they could be studied by classicists, while an attempt was made to reconstruct much of the original site. Although this was done in a manner that would be considered inappropriate today, it helped raise the profile of archaeology considerably.[38]

Modern methodology

[edit]See also

[edit]- Archaeology of Russia

- Archaeology of the Americas

- Council for British Archaeology

- History of anthropology

- Register of Professional Archaeologists

- List of Russian historians

- Outline of archaeology

- Typology (archaeology)

- Women in archaeology

- List of archaeological sites by country

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Silverberg, Robert (1997). Great Adventures in Archaeology. University of Nebraska Press. p. viii. ISBN 978-0-8032-9247-5.

- ^ a b c Kelly, Robert L.; Thomas, David Hurst (2013). Archaeology: Down to Earth. Cengage Learning. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-133-60864-6. Archived from the original on 22 December 2023. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ Watrall, Ethan. >. "ANP203-History-of-Archaeology-Lecture-2". Anthropology.msu.edu. Retrieved 7 April 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Hirst, K. Kris. "The History of Archaeology Part 1". ThoughtCo.com. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ "The History of the Science of Archaeology". Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- ^ Fairbank, John King; Goldman, Merle (2006) [1992], China: A New History (2nd enlarged ed.). Cambridge; London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-01828-1, p. 33.

- ^ a b Fraser, Julius Thomas; Haber, Francis C. (1986), Time, Science, and Society in China and the West. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, ISBN 0-87023-495-1, p. 227.

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66991-X (paperback), p. 148.

- ^ a b Clunas, Craig. (2004). Superfluous Things: Material Culture and Social Status in Early Modern China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2820-8, p. 95.

- ^ Trigger, Bruce G. (2006). A History of Archaeological Thought: Second Edition. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-84076-7, p. 74.

- ^ Trigger, Bruce G. (2006). A History of Archaeological Thought: Second Edition. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-84076-7, pp. 74–76.

- ^ Clunas, Craig. (2004). Superfluous Things: Material Culture and Social Status in Early Modern China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2820-8, p. 97.

- ^ Clunas, Craig. (2004). Superfluous Things: Material Culture and Social Status in Early Modern China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2820-8, pp. 95–97.

- ^ Rudolph, R.C. "Preliminary Notes on Sung Archaeology," The Journal of Asian Studies (Volume 22, Number 2, 1963): 171 (169–177).

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2009). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century (PB). Pearson Education. p. 13. ISBN 978-93-325-6996-6.

- ^ Ucko, P. J. (2005). Theory in Archaeology: A World Perspective. Taylor & Francis. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-134-84346-6. Archived from the original on 22 December 2023. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry; Davies, Wendy; Renfrew, Colin, eds. (2002). Archaeology: The Widening Debate. British Academy centenary monographs. British Academy. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-19-726255-9. Archived from the original on 22 December 2023. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ Livy, Ab Urbe Condita 7.3.7: cited also in the Oxford Latin Dictionary (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982, 1985 reprinting), p. 1132, entry on monumentum, as an example of meaning 4b, "recorded tradition."

- ^ El Daly, Okasha (2004). Egyptology: The Missing Millennium : Ancient Egypt in Medieval Arabic Writings. Routledge. p. 35. ISBN 1-84472-063-2.

- ^ J.A.White(ed),Biondo Flavio: Italy Illuminated (Cambridge, MA, 2005)

- ^ Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Flavio Biondo". Encyclopedia Britannica, 31 May. 2021, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Flavio-Biondo Archived 27 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 27 October 2021.

- ^ Edward W. Bodnar, Later travels, with Clive Foss. Harvard University Press, 2003. ISBN 9780674007581

- ^ Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "John Leland". Encyclopedia Britannica, 14 Apr. 2021, https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Leland Archived 22 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 27 October 2021.

- ^ Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "William Camden". Encyclopedia Britannica, 28 Apr. 2021, https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Camden Archived 27 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 27 October 2021.

- ^ Christina Bueno, The Pursuit of Ruins: Archeology, History, and the Making of Modern Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2016.

- ^ Hunter, Michael (1975). John Aubrey and the Realm of Learning. London: Duckworth. pp. 156–7, 162–6, 181. ISBN 0-7156-0818-5.

- ^ Hutton, Ronald (2009). Blood and Mistletoe: The History of the Druids in Britain. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300144857 p. 86.

- ^ Daniel J. Boorstin, The Discoverers, p. 584, Random House (New York, 1983).

- ^ Cole, Juan (2007). Napoleon's Egypt: Invading the Middle East. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-6431-1.

- ^ Dorothy King, The Elgin Marbles (Hutchinson, January 2006)

- ^ Everill, P. 2010. The Parkers of Heytesbury: Archaeological pioneers. Antiquaries Journal 90: 441–53

- ^ Everill, P. 2009. Invisible Pioneers. British Archaeology 108: 40–43

- ^ Bowden, Mark (1984) General Pitt Rivers: The father of scientific archaeology. Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum. ISBN 0-947535-00-4.

- ^ Hicks, Dan (2013). Hicks, Dan; Stevenson, Alice (eds.). Characterizing the World Archaeology Collections of the Pitt Rivers Museum. Oxford: Archaeopress. doi:10.2307/j.ctv17db2mz.7.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ "Sir William Flinders Petrie". Palestine Exploration Fund. 2000. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2007.

- ^ E.P. Uphill, "A Bibliography of Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie (1853–1942)," Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 1972 Vol. 31: 356–379.

- ^ Kenneth W. Harl. "Great Ancient Civilizations of Asia Minor". Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ MacGillivray, Joseph Alexander (2000). Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of the Minoan Myth. New York: Hill and Wang (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). ISBN 9780809030354.

Further reading

[edit]- Christenson, Andrew L., Tracing Archaeology's Past: The Historiography of Archaeology. Southern Illinois Univ Press, 1989.

- Kehoe, Alice Beck, The Land of Prehistory: A Critical History of American Archaeology. London: Routledge, 1998.

- Marchand, Suzanne L., Down from Olympus: Archaeology and Philhellenism in Germany, 1750 – 1970. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1996 (1st paperback ed. 2003).

- Pai, Hyung Il, Constructing "Korean" Origins: A Critical Review of Archaeology, Historiography, and Racial Myth in Korean State-Formation Theories. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000.

- Redman, Samuel J., Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016.

- William H. Stiebing Jr. Uncovering the Past: A History of Archaeology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Smith, Laurajane, Archaeological Theory and the Politics of Culture Heritage. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Trigger, Bruce, A History of Archaeological Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.