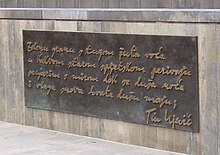

Tin Ujević

Tin Ujević | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Augustin Josip Ujević 5 July 1891 Vrgorac, Kingdom of Dalmatia, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 12 November 1955 (aged 64) Zagreb, PR Croatia, FPR Yugoslavia |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Language | Croatian |

| Nationality | Croat |

| Notable works | Lelek sebra Kolajna Auto na korzu Ojađeno zvono Žedan kamen na studencu |

| Signature | |

| |

Augustin Josip "Tin" Ujević (pronounced [auɡǔstin tîːn ûːjeʋitɕ]; 5 July 1891 – 12 November 1955) was a Croatian poet, considered by many to be the greatest poet in 20th century Croatian literature.[1][2]

From 1921, he ceased to sign his name as Augustin, thereafter using the signature Tin Ujević.[3]

Biography

[edit]Ujević was born in Vrgorac, a small town in the Dalmatian hinterland, and attended school in Imotski, Makarska, Split and Zagreb.[3] He completed Classical Gymnasium in Split, and in Zagreb he studied Croatian language and literature, classical Philology, Philosophy, and Aesthetics.[3]

In 1909, while studying literature, his first sonnet "Za novim vidicima" (Towards New Horizons) appeared in the journal Mlada Hrvatska (Young Croatia). After the assassination attempts on the ban Slavko Cuvaj in 1912, Ujević became active in the Nationalist youth movement and was repeatedly imprisoned.[3] On the eve of the First World War, he lived briefly in Dubrovnik, Šibenik, Zadar, Rijeka and for a longer time in Split. The crucial period for his political and poetic consciousness was his visit to Paris (1913–19).[3]

After the death of A.G. Matoš in 1914, Ujević published an essay about his teacher in the literary magazine Savremenik. That same year the anthology of poetry inspired by Matoš, "Hrvatska mlada lirika" (Croatian Young Lyrics) brought together the work of 12 young poets, including 10 poems by Tin Ujević.[3] Also in that year, Ujević joined the French Foreign Legion, though he left again after 3 months at the urging of Frano Supilo.[3]

In 1919, Ujević returned to Zagreb. Around that time he wrote two autobiographical essays "Mrsko Ja" (Hateful Me, 1922) examining his political beliefs, which he described as disenchanted, and "Ispit savjesti" (Examination of Conscience, published in 1923 in the journal Savremenik), which he himself called a "sleepwalking sketch". It is considered to be one of the most moving confessional texts in Croatian literature, in which an author mercilessly examines their own past.[3]

Ujević lived from 1920 to 1926 in Belgrade, then he moved between Split and Zagreb, back to Belgrade, then to Split again.[3] In 1920 his first anthology of poetry "Lelek sebra" (Cry of a slave) was published in Belgrade, and in 1922 his poem "Visoki jablani" (High Poplars) appeared in the journal Putevi (Roads).[3]

He was well known in bohemian circles in Belgrade and a frequent guest at Hotel Moskva and Skadarlija.[4][5]

During the years 1930–37, Ujević lived in Sarajevo, then 1937–1940 in Split, finally moving back to Zagreb, where he lived until his death in 1955.[3]

From 1941 to 1945 he did not publish a single book, earning his living as a journalist and translator.[6] Ujević held a post in the Independent State of Croatia as a translator, and continued to publish some material. For this reason, he was forbidden by the Yugoslav government from continuing with his literary career for several years.[7][8] In the last days of 1950 a selection of his work was published in Zagreb, under the title "Rukovet" ("Handful").[6] Ujević died on 12 November 1955 and is buried at Mirogoj Cemetery in Zagreb.[9]

Legacy

[edit]In addition to his poetry, Tin Ujević also wrote essays, short stories, serials (feuilletons), studies on foreign and domestic authors, and he translated philosophical discussions from many foreign languages.[3]

He translated numerous works of poetry, novels and short stories into Croatian (Edgar Allan Poe, Walt Whitman, Marcel Proust, Joseph Conrad, Benvenuto Cellini, George Meredith, Emile Verhaeren, Arthur Rimbaud, André Gide, among others[10]).

He wrote more than ten books of essays, poetry in prose and meditations — but his enduring strength lies chiefly in his poetic works. At first a follower of Silvije Strahimir Kranjčević and more especially A.G. Matoš, Ujević soon moved on and developed his own independent voice.[3]

He preferred the French and American modernists such as Charles Baudelaire, Arthur Rimbaud and Walt Whitman, whose work he translated. His first collections Lelek sebra, and Kolajna, inspired by his years in Paris, are considered the peak of modern Croatian lyrical poetry.[3]

From those original first books grew a body of work that is a classic of Croatian literature, and according to the British poet Clive Wilmer, "Tin Ujević was one of the last masters of European Symbolism".[10] Poet and writer Anne Stevenson says his "melancholy, turn-of-the-century lyricism" is comparable to that of Thomas Hardy, of Edward Thomas, and of early Yeats".[10]

British poet Richard Berengarten, who has translated some of Ujević's best works into English,[10] writes

"Although Tin's major achievement is as a lyricist, his oeuvre is much broader than lyric alone. He was a writer of profound and discerning intellect, broad and capacious interests, inquisitive appetite and eclectic range."

There are some 380 records about Tin Ujević's works in the catalogue of the National and University Library in Zagreb, and part of his literary heritage is preserved in the Library's Manuscripts and Old Books Collection. Ujević published his writings in all renowned newspapers and journals, in which numerous articles about Ujević were published, and part of that material in digital format is available at the Portal of Digitized Croatian Newspapers and Journals.[1]

The Tin Ujević Award is the most prestigious poetry award in Croatia.[11] In 2003, the Jadrolinija ferry, MV Tin Ujević was named for the poet.[citation needed] In 2005, Hrvatska Pošta issued a stamp in their series of Famous Croats: Tin Ujević on the 50th anniversary of his death.[6] By 2008, a total of 122 streets in Croatia were named after Ujević, making him the ninth most common person for whom streets were named in Croatia.[12] Six streets in Serbia are named after Ujević as of 2024[update].[13]

Works

[edit]

- Lelek sebra (Cry of a slave), 1920, Belgrade[14] (in Cyrillic, ekavian)

- Kolajna (Necklace), 1926, Belgrade (in Cyrillic, ekavian)

- Auto na korzu (Car on the promenade) 1932

- Ojađeno zvono (Heavy-hearted bell) 1933, Zagreb

- Skalpel kaosa (Scalpel of chaos) 1938, Zagreb

- Ljudi za vratima gostionice (People behind inn doors) 1938, Zagreb

- Žedan kamen na studencu (Thirsty stone at the wellspring), 1954, Zagreb

His collected works, Sabrana djela (1963–1967) were published in 17 volumes. Individually and within selected works, Izabrana djela, numerous editions of his poems, essays and studies were published.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "In Memory of Tin Ujević". National and University Library in Zagreb. Nacionalna i sveučilišna knjižnica u Zagrebu. 2012. Archived from the original on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

He was a poet and bohemian and, as the Fellow of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts Ante Stamać once said, without a doubt, the greatest poet in Croatian literature of the twentieth century.

- ^ Berengarten, Richard (2011). "A Nimble Footing on the Coals: Tin Ujević, Lyricist: Some English Perspectives". SIC Journal. Zadar University. doi:10.15291/sic/1.2.lt.4. ISSN 1847-7755. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Z. Zima (1997). Ujević, Tin (Augustin Josip). Hrvatski Leksikon (in Croatian). Vol. II. Zagreb: Naklada Leksikon d.o.o. p. 603. ISBN 978-953-96728-0-3.

- ^ "БЕОГРАДСКЕ ГОДИНЕ ТИНА УЈЕВИЋА | Politikin Zabavnik". politikin-zabavnik.co.rs. Retrieved 2020-04-23.

- ^ Vulićević, Marina. "Tin Ujević –najveći hrvatski boem u Skadarliji". Politika Online. Retrieved 2020-04-23.

- ^ a b c d "Famous Croats: 50th anniversary of the death of Augustin Tin Ujević". Hrvatska Pošta. 2005. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

In his feuilletons and essays Ujević demonstrated a huge, encyclopaedic knowledge of everything that he touched upon in his writing and pondering, whether he wrote about literature or philosophy, philology or politics, natural sciences of religious beliefs. He translated poetry and prose from numerous languages, and his translations can be counted among the ideal examples of mastery. His poetry and prose work is the uppermost achievement of Croatian literature from the first half of the 20th century.

- ^ Tin Ujević profile Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, knjiga.hr; accessed 29 April 2015.(in Croatian)

- ^ Fischer, Wladimir. "Die vergessene Nationalisierung. Eine synchrone und diachrone Analyse von Ritual, Mythos und Hegemoniekämpfen im jugoslavischen literaturpolitischen Diskurs von 1945 bis 1952." Dipl. Thesis. Universität Wien, 1997. Print. (in German)

- ^ Augustin Ujević Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Ujević, Tin (2013). Twelve Poems. Translated by Richard Berengarten; Daša Marić. Bristol, UK: Shearsman Chapbooks. ISBN 978-1-84861-316-4.

- ^ "DHK Nagrada Tin Ujevic". dhk.hr. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- ^ Letica, Slaven (29 November 2008). Bach, Nenad (ed.). "If Streets Could Talk. Kad bi ulice imale dar govora". Croatian World Network. ISSN 1847-3911. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ Адресни регистар at DATA.GOV.RS

- ^ Boško Novaković (1971). Živan Milisavac (ed.). Jugoslovenski književni leksikon [Yugoslav Literary Lexicon]. Novi Sad (SAP Vojvodina, SR Serbia: Matica srpska. p. 550-551.

External links

[edit]- Tin Ujević lyrics

- Translated works by Tin Ujević Archived 2014-05-28 at the Wayback Machine

- 1891 births

- 1955 deaths

- Croatian male poets

- Croatian essayists

- Croatian male essayists

- Croatian translators

- English–Croatian translators

- French–Croatian translators

- Italian–Croatian translators

- Burials at Mirogoj Cemetery

- People from Vrgorac

- Soldiers of the French Foreign Legion

- People of the Independent State of Croatia

- 20th-century Croatian poets

- 20th-century translators

- 20th-century essayists

- Croatian expatriates in France

- 20th-century male writers