Haverhill, New Hampshire

Haverhill, New Hampshire | |

|---|---|

Town | |

Haverhill municipal offices | |

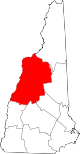

Location in Grafton County, New Hampshire | |

| Coordinates: 44°02′03″N 72°03′50″W / 44.03417°N 72.06389°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New Hampshire |

| County | Grafton |

| Incorporated | 1763 |

| Villages |

|

| Government | |

| • Selectboard |

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 52.4 sq mi (135.6 km2) |

| • Land | 51.0 sq mi (132.1 km2) |

| • Water | 1.4 sq mi (3.5 km2) 2.62% |

| Elevation | 640 ft (200 m) |

| Population (2020)[2] | |

| • Total | 4,585 |

| • Density | 90/sq mi (34.7/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | |

| Area code | 603 |

| FIPS code | 33-34820 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0873621 |

| Website | www |

Haverhill is a town and the seat of Grafton County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 4,585 at the 2020 census.[2] Haverhill includes the villages of Woodsville, Pike, and North Haverhill, the historic town center at Haverhill Corner, and the district of Mountain Lakes. Located here are Bedell Bridge State Park, Black Mountain State Forest, Kinder Memorial Forest, and Oliverian Valley Wildlife Preserve. It is home to the annual North Haverhill Fair, and to a branch of the New Hampshire Community Technical Colleges.

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2024) |

Settled by citizens from Haverhill, Massachusetts, the town was first known as "Lower Cohos". This Lower Cohos name is derived from the original Abenaki people who had a base for agriculture here. It was incorporated in 1763 by colonial Governor Benning Wentworth, and in 1773 became the county seat of Grafton County. Haverhill was the terminus of the old Province Road, which connected the northern and western settlements with the seacoast. By 1859, when the town had 2,405 inhabitants, industries included three gristmills, twelve sawmills, a paper mill, a large tannery, a carriage manufacturer, an iron foundry, seven shoe factories, a printing office, and several mechanic shops.[3] The town is home to the oldest documented covered bridge in the country still standing—the Haverhill–Bath Bridge, built in 1829.

The village of Woodsville, named for John L. Woods of Wells River, Vermont, was once an important railroad center. Woods operated a sawmill on the Ammonoosuc River, and developed a railroad supply enterprise following the establishment of the Boston, Concord & Montreal Railroad. The village of Pike was settled by future employees of the Pike Manufacturing Company, which was once the world's leading manufacturer of whetstones.

While the village of Haverhill Corner was historically considered to be the primary settlement in town, the town's municipal offices are currently located in the village of North Haverhill, with Grafton County's offices and courthouse located just two miles farther north along Route 10. The county seat offices were located in Woodsville until 1972, when the administrative offices relocated to rural land halfway between Woodsville and North Haverhill.

The village of Woodsville is now the commercial center of Haverhill and its smaller surrounding towns, including several in Vermont. Woodsville is home to the town's supermarkets, pharmacies, banks (including the headquarters of the regional Woodsville Guaranty Savings Bank), state liquor store, and most of its restaurants and chain stores, although a few are located in North Haverhill. The town's elementary and high schools, along with Cottage Hospital, a critical-access hospital serving the area, are all located in Woodsville.

-

Green Door Inn c. 1920

-

No Man's Island in 1913

-

East Haverhill in 1917

-

Court Street in 1910

Geography

[edit]Haverhill is in northwestern New Hampshire. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 52.4 square miles (135.6 km2), of which 51.0 square miles (132.1 km2) are land and 1.4 square miles (3.5 km2) are water, comprising 2.62% of the town.[1] Bounded on the west by the Connecticut River, which forms the state border with Vermont, Haverhill is drained by the Ammonoosuc River, in addition to Oliverian Brook and Clark Brook. Haverhill lies fully within the Connecticut River watershed.[4]

The highest point in Haverhill, at 2,320 feet (710 m) above sea level, is on the western slope of Black Mountain, whose 2,830 ft (860 m) summit is in the neighboring town of Benton.

The town is served by six state-maintained routes. New Hampshire Route 10 is the main north–south highway through Haverhill, paralleling the Connecticut River. U.S. Route 302 enters from Vermont and passes east–west through Woodsville in the northern part of town, joining with Route 10 to head northeast to Bath and Littleton. New Hampshire Route 25 enters Haverhill from Piermont while co-signed with Route 10, splitting off by itself to the southeast in Haverhill Corner. New Hampshire Route 116 has its southern terminus at Route 10 in North Haverhill, and New Hampshire Route 135 has its southern terminus at Route 10 just south of Woodsville. A very short section of New Hampshire Route 112 passes through the northeastern part of town. Haverhill also has easy access to U.S. Route 5 via bridges in North Haverhill and Woodsville.

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 552 | — | |

| 1800 | 805 | 45.8% | |

| 1810 | 1,105 | 37.3% | |

| 1820 | 1,609 | 45.6% | |

| 1830 | 2,183 | 35.7% | |

| 1840 | 2,675 | 22.5% | |

| 1850 | 2,405 | −10.1% | |

| 1860 | 2,291 | −4.7% | |

| 1870 | 2,271 | −0.9% | |

| 1880 | 2,455 | 8.1% | |

| 1890 | 2,545 | 3.7% | |

| 1900 | 3,414 | 34.1% | |

| 1910 | 3,498 | 2.5% | |

| 1920 | 3,406 | −2.6% | |

| 1930 | 3,665 | 7.6% | |

| 1940 | 3,487 | −4.9% | |

| 1950 | 3,357 | −3.7% | |

| 1960 | 3,127 | −6.9% | |

| 1970 | 3,090 | −1.2% | |

| 1980 | 3,445 | 11.5% | |

| 1990 | 4,164 | 20.9% | |

| 2000 | 4,416 | 6.1% | |

| 2010 | 4,697 | 6.4% | |

| 2020 | 4,585 | −2.4% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[2][5] | |||

As of the census of 2010, there were 4,697 people, 1,928 households, and 1,208 families residing in the town. There were 2,379 housing units, of which 451, or 19.0%, were vacant. 294 of the vacant units were for seasonal or recreational use. The racial makeup of the town was 96.7% white, 0.4% African American, 0.4% Native American, 0.9% Asian, 0.1% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, 0.3% some other race, and 1.2% from two or more races. 1.3% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.[6]

Of the 1,928 households, 26.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 48.5% were headed by married couples living together, 9.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 37.3% were non-families. 29.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.4% were someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.29, and the average family size was 2.80.[6]

In the town, 19.4% of the population were under the age of 18, 7.4% were from 18 to 24, 23.4% from 25 to 44, 31.3% from 45 to 64, and 18.7% were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 45.0 years. For every 100 females, there were 97.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.9 males.[6]

For the period 2011–2015, the estimated median annual income for a household was $48,405, and the median income for a family was $56,100. Male full-time workers had a median income of $42,363 versus $33,150 for females. The per capita income for the town was $24,493. 15.1% of the population and 9.9% of families were below the poverty line. 26.7% of the population under the age of 18 and 5.3% of those 65 or older were living in poverty.[7]

Sites of interest

[edit]- Bedell Bridge State Park[8]

- Haverhill-Bath Covered Bridge (1829)[9]

- Haverhill Historical Society & Museum[10]

- Museum of American Weather[11]

- Oliverian School

- Clement Farm Disc Golf Course

Notable people

[edit]- George Barstow (1824–1883), California politician

- Samuel Brooks (c. 1793–1849), merchant, politician in Lower Canada

- Noah Davis (1818–1902), U.S. congressman

- Henry W. Keyes (1863–1938), 56th governor of New Hampshire

- Ebenezer Mackintosh (1737–1816), leader in Boston Stamp Act riots

- Thomas Leverett Nelson (1827–1897), judge

- John Page (1787–1865), governor of New Hampshire, U.S. senator

- John A. Page (1814–1891), son of Governor and Senator John Page, Vermont State Treasurer

- Chad Paronto (born 1975), relief pitcher with the Baltimore Orioles, Cleveland Indians, Atlanta Braves, and Houston Astros[12]

- Jonathan H. Rowell (1833–1908), U.S. congressman from Illinois

- Bob Smith (1931–2013), pitcher with the Boston Red Sox, St. Louis Cardinals, Pittsburgh Pirates, and Detroit Tigers[13]

- Mark Steyn (born 1959), writer, political commentator[14]

- Frank Stoddard, crew chief with NASCAR[15]

Incident

[edit]Maura Murray disappeared on the evening of February 9, 2004, after a car crash on New Hampshire Route 112 near Woodsville.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "2021 U.S. Gazetteer Files – New Hampshire". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Haverhill town, Grafton County, New Hampshire: 2020 DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171)". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ Coolidge, Austin Jacobs; Mansfield, John Brainard (1859). "A. J. Coolidge & J. B. Mansfield, A History and Description of New England; Boston, Massachusetts 1859". Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ^ Foster, Debra H.; Batorfalvy, Tatianna N.; Medalie, Laura (1995). Water Use in New Hampshire: An Activities Guide for Teachers. U.S. Department of the Interior and U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (DP-1): Haverhill town, Grafton County, New Hampshire". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ "Selected Economic Characteristics: 2011–2015 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates (DP03): Haverhill town, Grafton County, New Hampshire". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ "Archived copy". www.nhstateparks.org. Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "BATH-HAVERHILL BRIDGE – New Hampshire Covered Bridges". Archived from the original on February 20, 2009. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- ^ "Historical Society". October 5, 2010. Archived from the original on October 5, 2010. Retrieved November 8, 2021.

- ^ "NH Attractions - Museum of American Weather - NewHampshire.com". August 8, 2008. Archived from the original on August 8, 2008. Retrieved November 8, 2021.

- ^ "Chad Paronto Stats | Baseball-Reference.com". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on July 12, 2017. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- ^ "Bob Smith Stats | Baseball-Reference.com". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on July 13, 2017. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- ^ "My Kind of Town". National Review. September 20, 2011. Archived from the original on September 24, 2011. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ^ Myers, Bob (February 2009). "NASCAR Crew Chief Frank Stoddard". Circle Track. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2011.