Bordesley Green

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2011) |

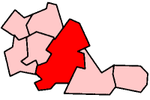

| Bordesley Green | |

|---|---|

South & City College Birmingham – Bordesley Green Campus | |

Location within the West Midlands | |

| Population | 33,937 (Ward population in 2011) |

| • Density | 81.25 per ha |

| OS grid reference | SP105865 |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Shire county | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BIRMINGHAM |

| Postcode district | B9/B10 |

| Dialling code | 0121 |

| Police | West Midlands |

| Fire | West Midlands |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Bordesley Green is an inner-city area of Birmingham, England about two miles east of the city centre. It also contains a road of the same name. It is in the Bordesley Green Ward which also covers some of Small Heath and Little Bromwich. Bordesley Green East is in the Heartlands Ward.

Heartlands Hospital is located in the eastern part of Bordesley Green. The area is also served by Yardley Green Medical Centre and Omnia Practice.

Kingfisher Country Park covers the River Cole recreation grounds which are partially covered by the area's boundaries.

Bordesley Green has a larger Eastern European community including Romanians, Poles, and Russians settling in the area, but it is still predominantly South Asian.[not verified in body]

History

[edit]The name of this part of Birmingham is derived from an ancient area of demesne pasture, listed in early records dating back to 1285 as La Grene de Bordeslei.[1]

The area began to be built up in 1834, with scattered developments from Bordesley along Bordesley Green from the junction of Cattell Road and Garrison Lane as far east as Blake Lane. By 1906 urban development had spread eastwards as far as Blakesland Street and Mansell Road and included a fire station and police station, both of which survive, though the fire station no longer serves its original purpose and the police station is now a hostel for homeless people.[2][3]

Many roads in Bordesley Green were built not long after the Boer War at the end of the 19th century and were named to commemorate the hundreds of soldiers from Birmingham that died in that war.[4] Examples include Pretoria Road, named after the capital of the Boer republic of the Transvaal; Churchill Road, after Winston Churchill who fought in the Boer War, was captured but escaped; Botha Road, named after the Boer general who became the first prime minister of the Union of South Africa; and Colonial Road.[5]

Many late-Victorian and Edwardian houses remain in Bordesley Green and much of the area has physically changed little since then.

Industrial Hub

[edit]At the turn of the twentieth century Bordesley Green had become a district noted for industry and manufacturing. It was the home from 1901 to 1920 of the Wolseley Tool and Motor Car Company's motor cars and machine tools manufacturing plant.[6]

The National Telephone Company's depot in Fordrough Lane came to be one of the three major General Post Office (GPO) factories in Birmingham. The factory specialised in manual telephony, including factory repaired telephones, "candlestick" ‘phones, switchboards and associated components, and played a significant role in the development of the Colossus computer used to read encrypted German messages in World War II.[7]

In the 1960s, the HANDEL Nuclear Attack Warning equipment, known as the four minute warning was manufactured in Bordesley Green, along with equipment for regional seats of government, which were part of Britain's civil defence preparations for nuclear war.[8]

Blitz

[edit]Bordesley Green was targeted during the Blitzkrieg with five raids hitting the area. The last German bomb to hit Birmingham landed on 24 April 1943 and hit Bordesley Green.[9]

The GPO factory was also hit by German bombing raids in 1940.[10]

Geography

[edit]Wildlife

[edit]Tumbling Pigeons

[edit]In the 1920s a Bordesley Green bus driver and pigeon fancier, William Penson,[11] noticed one of his birds perform a backflip while in flight, and through selective breeding produced the Roller and Tumbler breed of pigeon.[12] This breed is noted for its unique acrobatics while in flight and is used in ‘parlour rolling’ contests. Today there are hundreds of Birmingham Roller clubs around the world and fiercely fought competitions to pick the birds that perform the most dramatic tumbling.[13]

Geology

[edit]The bedrock geology of the area consists predominantly of Sidmouth Mudstone Formation. Sedimentary Bedrock formed approximately 228 to 250 million years ago in the Triassic Period. The local environment was previously dominated by hot deserts. The types of sedimentary rocks in the Bordesley area are fluvial, lacustrine and marine in origin. They would have been detrital, deposited in lagoons or shallow seas, where a hot, arid climate would have led to the precipitation of beds of evaporites.

The superficial deposits tend to be glaciofluvial in origin, Mid Pleistocene - Sand And Gravel. Superficial Deposits in area were formed up to 2 million years ago in the Quaternary Period. The Bordesley environment would have been dominated by ice age conditions. The deposits are detrital, generally coarse-grained, forming beds, channels, plains and fans associated with meltwater.[14]

Lost brook of Bordesley Green

[edit]Early maps of the area show a brook which extended from Shaw Hill down to Bordesley Green Road, which is now mostly submerged, with the exception of a small section which emerges from a culvert in Bordesley Green. It is called Washbrook. It starts up near Garrison Lane, then flows through the South African Estate, on through the allotments. It is open in Ward End Park then on into the River Tame at Bromford.[15]

Demography

[edit]In 2001, an estimated 31,343 people were living in the ward making it the second most populous ward, behind Sparkbrook.[16] This increased to 33,937 by the time of the 2011 Population Census. The ward has an area of 417.7 hectares resulting in a population density of 81.25 people per hectare.[17] Females represent 51.2% of the population, below the city average of 51.6% and the national average of 51.3%.

99.7% of residents lived in households, above the city average of 98.3%. The other 0.3% lived in communal establishments. The total number of occupied households in the ward was 9,350. This results in an average of number of people per household of 3.3, higher than the city of 2.5 and national average of 2.4. The majority of households are owner occupied (58%). 20.6% of occupied households are rented from Birmingham City Council, above the city average of 19.4%. 337 houses were identified as being vacant. Terraced houses built in the late 19th or early 20th century were the most common form of housing in the area at 54.4%, compared with the city average of 31.3% and the national average of 25.8%. At 25.4%, semi-detached houses were the second most common form of housing.

The area is home to an ethnically diverse community and ethnic minorities comprise 71.1% of the population compared to 29.6% for Birmingham overall. 33.5% of the population was born outside of the United Kingdom, much higher than the city average of 16.5% and the national average of 9.3%. 62.2% of the population was of Asian origin, of which 50.5% were British Pakistanis.[citation needed] The proportion of Asian people in Birmingham is much lower at 19.5% and the proportion of Pakistani people is 10.6%. White British people represented 25.7% of the ward's population. There is a wide variety of languages spoken within the area such as Punjabi, Urdu, Mirpuri, Bengali, Pushto and Arabic with English being the most widely spoken language. The most dominant religion in the ward was Islam with 59.4% of the population stating themselves as Muslims, above the average for Birmingham of 14.3% and the national average of 3.1%.[citation needed] Christianity was the second largest religion in the ward with 27.1% of the ward's population stating themselves as Christians.[citation needed]

The ethnic minorities of Bordesley Green are particularly concentrated in the Victorian and Edwardian terraced houses, having emigrated to the area from the Commonwealth during the 1950s and 1960s.[citation needed]

The 25–44 age group represented the greatest portion of all age groups at 27.3%.[citation needed] At 22.2%, the 5–15 age group was the second largest. The proportion of the population that was of a pensionable age was 11.7%, below the city average of 16.7% and the national average of 18.4%.[citation needed] The proportion of people of a working age was 54.9%, below the city average of 59.8% and national average of 61.5%.[citation needed] The unemployment rate is 15.5%, higher than the city average of 9.5% and national average of 5%. 47.1% of the residents were identified as being economically active.[citation needed] Of the unemployed, 34.1% were in long term unemployment and 23.6% had never worked. 19.5% of the working population worked in the Wholesale & Retail Trade, Vehicle Repairs sector, followed by 19.3% of the working population working in the Manufacturing sector.[citation needed] The Birmingham Heartlands & Solihull Trust is the largest employer in the area, employing approximately 5,000 people. South Birmingham College is the second largest employer, employing around 850 people.[18]

Several hundred terraced houses around Bordesley Green dating from the late 19th and early 20th centuries were demolished in the early 1990s and new houses built on their site as part of a "New homes for old" initiative which allowed people to remain living in areas that their families had lived in for generations.

Politics

[edit]The Bordesley Green Ward was created in June 2004 out of the Small Heath and Sparkbrook wards. However the 2004 council election was marred by vote rigging by the Labour Party candidates, who were subsequently removed from the council.

The ward has been represented on Birmingham City Council by Labour councillor Raqeeb Aziz since 2022.[19]

Bordesley Village

[edit]Bordesley Green has a neighbouring village, Bordesley Village, offering considerably better housing. The village is often referred as a separate area, and attempts are being made to separate the two to distinguish the areas. The village is also home to the city's football team, Birmingham City FC, built before the village was established from an old gypsy encampment and scrap yard. Recently, the village has seen several additions, becoming the hub of the city's new car sales and many more national companies within walking distance of the village.

The Village concept in Bordesley Green was the first "Ideal Village" in England, built between 1908 and 1914 by Barry Parker and Raymond Unwin. The pair eventually went on to build Welwyn Garden City in Hertfordshire. The villages were a welcome relief to English cities at the time and the homes were built to high standards.

Daniels Road in Bordesley Green commemorates schoolteacher Francis Daniels. Originally from Ebley near Stroud, Daniels came to Birmingham in 1891 and soon saw the need to provide affordable social security for ordinary working people. With the Lord Mayor, Alderman William Kendrick as president and Daniels himself as general secretary, the Ideal Society was formed.

By 1910 the society had moved into housing provision and commenced the building of the Ideal Village at Bordesley Green, where Finnemore Road also commemorates an early chairman of the society, William Finnemore. The first houses to be built were in Drummond Road. The village, which was designed for artisan workers, has shops, a park and a school and a much lower density of housing than the nearby terraces.

St Paul's Mission, built in 1912 in Finnemore Road as a chapel of St Margaret's Ward End, was consecrated as a parish church in 1929. A new church was built c1970 in Belchers Lane behind the old, which was retained as the church hall. The church is now the centre of a community project embracing a number of different facilities and services.

In 1998 children from Bordesley Green Primary School discovered the origin of a badly damaged stone fountain in the Ideal Park which commemorates the rescue by a local boy of a drowning girl. On 7 May 1907 16-year-old cycle polisher, Harold Clayfield of 11 Ronald Road, jumped into a 5m deep clay pit at the junction of Belchers Lane and Bordesley Green to save 4-year-old, Florence Jones. The girl was saved, but non-swimmer Clayfield, drowned. His memorial was paid for by public subscription. Sadly Florence herself was to die only four years later as a result of playing with burning pieces of paper at her home in Green Lane.[20]

Public art

[edit]The area features public art with the installation of Ondré Nowakowski's Sleeping Iron Giant, a large head lying on its side on a mound near the St Andrew's football ground.

Skate park

[edit]Bordesley Green has one skate park, known locally as the Pod. It is popular with mini BMX Rocker riders.[21]

Bordesley Green Allotments

[edit]The historic Bordesley Green Allotments is a 25-acre site that is host to the Bordesley Green Forest garden[22][non-primary source needed] and in 2012 was the venue for the Birmingham Annual Gardening Show[23] which is normally held in Kings Heath Park.

Education

[edit]Primary schools

[edit]- Alston Junior and Infants Primary School

- Bordesley Green Junior and Infants Primary School

- Wyndcliffe Primary School

Secondary schools

[edit]Further education

[edit]- South and City College Birmingham – Bordesley Green Campus

Health

[edit]- Heartlands Hospital

- Yardley Green Medical Centre

- Omnia Practice

Birmingham Wheels Park

[edit]Bordesley Green is home to Birmingham Wheels Park, a community motor sport facility that includes an oval race track, outdoor go-kart track, roller derby track, rally school and drifting track. Up to 5,000 people attended the oval track during its most popular stock car and banger racing meetings, while the speed skating team were multiple British champions in various age disciplines and the most successful roller speed club in the UK.[citation needed] In 2020, the operators announced that the site was under threat of closure due to failure to reach an agreement with the freeholders, Birmingham City Council, over plans to redevelop the area. The park closed for good on 31 October 2021.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ "Placenames Gazetteer".

- ^ "The old fire station in Bordesley Green".

- ^ "Old police station in Bordesley Green".

- ^ "Birmingham Boer War Memorial".

- ^ "Birmingham History".

- ^ "In production : Adderley Park Wolseley Works". February 2017.

- ^ "Birmingham's role in cracking the Nazi Enigma code". Birmingham Post. 18 August 2008.

- ^ "GPO".

- ^ "Birmingham in the Blitz: Where the bombs fell". 2 November 2010.

- ^ "Birmingham History Forum".

- ^ "THE BIRMINGHAM ROLLER PIGEON by William Penson".

- ^ "Rolling and Tumbling in Pigeons". Universities Federation for Animal Welfare.

- ^ "British Eccentrics - Maybe It Is Everyone Else Who Is Out Of Step". Huffington Post. 13 October 2011.

- ^ "Geology of Britain viewer | British Geological Survey (BGS)".

- ^ "OS Six-inch England and Wales, 1842-1952".

- ^ Birmingham Economy: Population[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Bordesley Green Ward Fact Sheet" (PDF).

- ^ Birmingham Economy: Bordesley Green[permanent dead link]

- ^ Council, Birmingham City. "Councillors by Ward: Bordesley Green". Birmingham City Council. Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "The Ideal Village". billdargue.jimdo.com.

- ^ "Launch of 'The POD' and Skate Park". Launch of 'The POD' and Skate Park @ 1 Geranium Grove. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ^ "Bordesley Green Forest Garden". Facebook.

- ^ "Birmingham Annual Gardening". BBC News. 16 August 2012.

- ^ "Birmingham Wheels Park is to close after the city council won funding to regenerate the area". ITV.com. ITV Consumer Limited. 31 October 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2022.