Deadwood, South Dakota

Deadwood, South Dakota

Owáyasuta | |

|---|---|

Modern Deadwood viewed from Mount Moriah | |

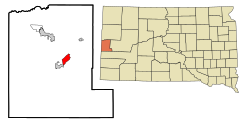

Location in Lawrence County and the state of South Dakota | |

| Coordinates: 44°23′13″N 103°43′15″W / 44.38694°N 103.72083°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | South Dakota |

| County | Lawrence |

| Founded | April 1876 |

| Incorporated | February 22, 1881[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | City Commission |

| • Mayor | David R. Ruth Jr. |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4.929 sq mi (12.767 km2) |

| • Land | 4.929 sq mi (12.767 km2) |

| • Water | 0.000 sq mi (0.000 km2) |

| Elevation | 4,715 ft (1,437 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 1,156 |

| • Estimate (2023)[5] | 1,343 |

| • Density | 272.0/sq mi (105.2/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC–7 (Mountain (MST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC–6 (MDT) |

| ZIP Code | 57732 |

| Area code | 605 |

| FIPS code | 46-15700 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1267350[3] |

| Sales tax | 6.2%[6] |

| Website | cityofdeadwood.com |

Deadwood Historic District | |

| Architectural style | Neoclassical, Late Victorian |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000716[7] |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

Deadwood (Lakota: Owáyasuta;[8][failed verification] "To approve or confirm things") is a city that serves as county seat of Lawrence County, South Dakota, United States. It was named by early settlers after the dead trees found in its gulch.[9] The city had its heyday from 1876 to 1879, after gold deposits had been discovered there, leading to the Black Hills Gold Rush. At its height, the city had a population of 25,000,[10] attracting Old West figures such as Wyatt Earp, Calamity Jane, Seth Bullock and Wild Bill Hickok (who was killed there).

The entire town has been designated as a National Historic Landmark District, for its well-preserved Gold Rush-era architecture. The town has five unique history museums that operated by Deadwood History, inc., a non-profit organization. Deadwood's proximity to Lead often prompts the two towns being collectively named "Lead-Deadwood".

The population was 1,156 at the 2020 census,[4] and according to 2023 census estimates, the city is estimated to have a population of 1,343.[5]

History

[edit]19th century

[edit]The settlement of Deadwood began illegally in the 1870s, on land which had been granted to the Lakota people in the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie. The treaty had guaranteed ownership of the Black Hills to the Lakota people, who consider this area to be sacred. The settlers' squatting led to numerous land disputes, several of which reached the United States Supreme Court.

Everything changed after Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer was ordered to lead an expedition into the Black Hills and announced the discovery of gold in 1874, on French Creek near present-day Custer, South Dakota. This announcement was a catalyst for the Black Hills Gold Rush, and miners and entrepreneurs swept into the area. They created the new and lawless town of Deadwood, which quickly reached a population of approximately 5,000. By 1877, about 12,000 people settled in Deadwood,[11] while other sources put the peak number even at 25,000 in 1876.[10]

In early 1876, frontiersman Charlie Utter and his brother Steve led to Deadwood a wagon train containing what they believed were needed commodities, to bolster business. The town's numerous gamblers and prostitutes staffed several profitable ventures. Madame Mustache and Dirty Em were on the wagon train, and set up shop in what was referred to as Deadwood Gulch.[12] Women were in high demand by the miners, and the business of prostitution proved to have a good market. Madam Dora DuFran eventually became the most profitable brothel owner in Deadwood, closely followed by Madam Mollie Johnson.

Deadwood became known for its lawlessness; murders were common, and justice for murders not always fair and impartial.[13] The town attained further notoriety when gunman Wild Bill Hickok was killed on August 2, 1876. Both he and Calamity Jane were buried at Mount Moriah Cemetery, as well as other notable figures such as Seth Bullock.

Hickok's murderer, Jack McCall, was prosecuted twice, despite the U.S. Constitution's prohibition against double jeopardy. Because Deadwood was an illegal town in Indian Territory, non-native civil authorities lacked the jurisdiction to prosecute McCall. McCall's trial was moved to a Dakota Territory court, where he was found guilty of murder and hanged.

Beginning August 12, 1876, a smallpox epidemic swept through. So many people fell ill that tents were erected to quarantine the stricken.

In 1876, General George Crook pursued the Sioux Indians from the Battle of Little Big Horn, on an expedition that ended in Deadwood in early September, known as the Horsemeat March. The same month, businessman Tom Miller opened the Bella Union Saloon.

On April 7, 1877, Al Swearengen, who controlled Deadwood's opium trade, also opened a saloon; his was called the Gem Variety Theater. The saloon burned down and was rebuilt in 1879. When it burned down again in 1899, Swearengen left town.

As the economy changed from gold panning to deep mining, the individual miners went elsewhere or began to work in other fields. Hence Deadwood lost some of its rough and rowdy character, and began to develop into a prosperous town.

The Homestake Mine in nearby Lead was established in October 1877. It operated for more than a century, becoming the longest continuously operating gold mine in the United States. Gold mining operations did not cease until 2002. The mine has been open for visiting by tourists.

On September 26, 1879, a fire devastated Deadwood, destroying more than 300 buildings and consuming the belongings of many inhabitants. Many of the newly impoverished left town to start again elsewhere.

In 1879, Thomas Edison demonstrated the first successful incandescent lamp in New Jersey, and on September 17, 1883, Judge Squire P. Romans took a gamble and founded the "Pilcher Electric Light Company of Deadwood". He ordered an Edison dynamo, wiring, and 15 incandescent lights with globes. After delays, the equipment arrived without the globes. Romans had been advertising an event to show off the new lights and decided to continue with the lighting, which was a success. His company grew. Deadwood had electricity service less than four years after Edison commercialized it, less than a year after commercial service was started in Roselle, New Jersey, and around the same time that many larger cities around the country established the service.[14]

In 1888, J.K.P. Miller and his associates founded a narrow-gauge railroad, the Deadwood Central Railroad, to serve their mining interests. In 1893, Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad purchased the railroad. In 1902, a portion of the railroad between Deadwood and Lead was electrified for operation as an interurban passenger system, which operated until 1924. In 1930, the railroad was abandoned, apart from a portion from Kirk to Fantail Junction, which was converted to standard gauge. In 1984, Burlington Northern Railroad abandoned the remaining section.[15]

Some of the other early town residents and frequent visitors included Martha Bullock, Aaron Dunn, E. B. Farnum, Samuel Fields, A. W. Merrick, Dr. Valentine McGillycuddy, Reverend Henry Weston Smith, Sol Star, and Charlie and Steve Utter.

Chinatown

[edit]The gold rush attracted Chinese immigrants to the area; their population peaked at 250.[16] A few engaged in mining; most worked in service enterprises. A Chinese quarter arose on Main Street, as there were no restrictions on foreign property ownership in Dakota Territory, and a relatively high level of tolerance of different peoples existed in the frontier town. Wong Fee Lee arrived in Deadwood in 1876 and became a leading merchant. He was a community leader among the Chinese Americans until his death in 1921.[17]

The quarter's residents also included African Americans and European Americans.[18] During the 2000s, the state sponsored an archeological dig in the area, to study the history of this community of diverse residents.[19]

20th and 21st centuries

[edit]Another major fire in September 1959 nearly destroyed the town again. About 4,500 acres (1,800 ha) were burned and an evacuation order was issued. Nearly 3,600 volunteer and professional firefighters, including personnel from the Homestake Mine, Ellsworth Air Force Base, and the South Dakota National Guard's 109th Engineer Battalion, worked to contain the fire. The property losses resulted in a major regional economic downturn.[20][21]

In 1961, the entire town was designated a National Historic Landmark, for its well-preserved collection of late 19th-century frontier architecture. Most of the town's buildings were built before 1900, with only modest subsequent development.[22] The town's population continued to decline through the 1960s and 1970s.[23] Interstate 90 bypassed Deadwood in 1964, diverting travelers and businesses. On May 21, 1980, a raid by county, state, and federal agents on the town's three remaining brothels—"The White Door", "Pam's Purple Door" and "Dixie's Green Door"—accomplished, as one reporter put it, "what Marshal Hickok never would have done",[24] and the houses of prostitution were padlocked.[23]

A fire in December 1987 destroyed the historic Syndicate Building and a neighboring structure.[23] The fire prompted renewed interest in the area and hopes for redevelopment. Organizers planned the "Deadwood Experiment," in which gambling was tested as a means to stimulate growth in the city center.[23][25] At the time, gambling was legal only in the state of Nevada and in Atlantic City.[26]

Deadwood was the first small community in the U.S. to seek legal gambling revenue to maintain local historic assets.[26] The state legislature legalized gambling in Deadwood in 1989, which generated significant new revenue and development.[27] The pressure of development since then may have an effect on the historical integrity of the landmark district.[27] Heritage tourism is important for Deadwood and the state.

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 4.929 square miles (12.77 km2), all land.[2]

Recreation

[edit]In the summer, there are numerous trails for hiking, horseback riding, and mountain biking. The northern end of the George S. Mickelson Trail starts in Deadwood and runs south through the Black Hills to Edgemont. Several man made lakes, including Sheridan Lake, provide fishing and swimming. Spearfish Canyon to the north has many places to rock climb. In early June, the Mickelson Trail Marathon and 5K, as well as accompanying races for children, are held.[citation needed] During the winter, two ski areas operate just a few miles outside of nearby Lead, South Dakota: Terry Peak and Deer Mountain.

The Midnight Star was a casino in Deadwood owned by American film actor Kevin Costner. The casino opened in the spring of 1991, after Costner had directed and starred in the Academy Award-winning film Dances With Wolves (1990), which was filmed mainly in South Dakota. The Midnight Star was a saloon which featured prominently in the previous western Costner had acted in, Silverado (1985), one of his first major roles. International versions of many of his films' posters lined the walls. The casino closed in August 2017.[28]

Climate

[edit]Deadwood's climate varies considerably from the rest of the state and surrounding areas. While most of the state receives less than 25 inches (640 mm) of precipitation per year, annual precipitation in the Lead—Deadwood area reaches nearly 30 inches (760 mm). Despite a mean annual snowfall of 102.9 inches (2.6 m), warm chinook winds are frequent enough that the median snow cover is zero even in January, although during cold spells after big snowstorms there can be considerable snow on the ground. On November 6, 2008, after a storm had deposited 45.7 inches (1.2 m) of snow, with a water equivalent of 4.25 inches (108 mm), 35 inches (0.9 m) of snow lay on the ground.[29]

Spring is brief, and is characterized by large wet snow storms and periods of rain. April 2006, although around 4 °F (2.2 °C) hotter than the long-term mean overall, saw a major storm of 54.4 inches (1.4 m), with a water equivalent 4.3 inches (109 mm), and left a record snow depth of 39 inches (1 m) on the 19th. Typically the first 70 °F (21 °C) temperature will be reached at the beginning of April, the first 80 °F (27 °C) near the beginning of May, and the first 90 °F (32 °C) around mid-June. Despite the fact that warm afternoons begin occasionally so early, 192.4 mornings each year fall to or below freezing, and even in May 8.8 mornings reach this temperature. Over the year, 0 °F or −17.8 °C is reached on 12.9 mornings per year, and 39.1 afternoons do not top freezing. The spring season sees heavy snow and rainfall, with 34 inches (0.9 m) of snow having fallen in April 1986 and as much as 15.99 inches (406 mm) of precipitation in the record wet May 1982.

The summer season is very warm, although with cool nights: only 14.7 afternoons equal or exceed 90 °F (32.2 °C). Rainfall tapers off during the summer: August 2000 was one of only two months in the 30-year 1971 to 2000 period to see not even a trace of precipitation. The fall is usually sunny and dry, with increasingly variable temperatures.

| Climate data for Deadwood, South Dakota, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1909–2006 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 65 (18) |

68 (20) |

78 (26) |

91 (33) |

94 (34) |

101 (38) |

103 (39) |

103 (39) |

101 (38) |

89 (32) |

75 (24) |

67 (19) |

103 (39) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 38.0 (3.3) |

38.8 (3.8) |

48.0 (8.9) |

54.8 (12.7) |

64.6 (18.1) |

75.3 (24.1) |

82.9 (28.3) |

81.8 (27.7) |

72.9 (22.7) |

58.3 (14.6) |

47.1 (8.4) |

37.9 (3.3) |

58.4 (14.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 26.2 (−3.2) |

26.5 (−3.1) |

35.0 (1.7) |

42.3 (5.7) |

51.7 (10.9) |

62.2 (16.8) |

69.4 (20.8) |

67.7 (19.8) |

58.5 (14.7) |

44.8 (7.1) |

34.5 (1.4) |

26.2 (−3.2) |

45.4 (7.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 14.4 (−9.8) |

14.2 (−9.9) |

21.9 (−5.6) |

29.8 (−1.2) |

38.9 (3.8) |

49.1 (9.5) |

55.8 (13.2) |

53.6 (12.0) |

44.1 (6.7) |

31.4 (−0.3) |

21.9 (−5.6) |

14.5 (−9.7) |

32.5 (0.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −30 (−34) |

−29 (−34) |

−22 (−30) |

−6 (−21) |

2 (−17) |

23 (−5) |

32 (0) |

27 (−3) |

14 (−10) |

−7 (−22) |

−16 (−27) |

−29 (−34) |

−30 (−34) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.35 (34) |

1.19 (30) |

1.72 (44) |

3.55 (90) |

5.04 (128) |

3.77 (96) |

2.72 (69) |

2.18 (55) |

2.06 (52) |

3.36 (85) |

1.38 (35) |

1.43 (36) |

29.75 (754) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 12.3 (31) |

13.2 (34) |

18.2 (46) |

19.8 (50) |

1.2 (3.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.9 (2.3) |

4.6 (12) |

15.3 (39) |

15.7 (40) |

101.2 (257.3) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.4 | 6.3 | 7.9 | 9.1 | 11.8 | 11.7 | 9.7 | 6.7 | 6.7 | 6.4 | 5.7 | 6.4 | 94.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 5.9 | 5.8 | 6.0 | 2.8 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 3.9 | 5.7 | 32.3 |

| Source 1: NOAA (precip/precip days, snow/snow days 1981–2010)[30][31] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: XMACIS2[32] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 3,777 | — | |

| 1890 | 2,366 | −37.4% | |

| 1900 | 3,408 | 44.0% | |

| 1910 | 3,653 | 7.2% | |

| 1920 | 2,403 | −34.2% | |

| 1930 | 2,559 | 6.5% | |

| 1940 | 4,100 | 60.2% | |

| 1950 | 3,288 | −19.8% | |

| 1960 | 3,045 | −7.4% | |

| 1970 | 2,409 | −20.9% | |

| 1980 | 2,035 | −15.5% | |

| 1990 | 1,830 | −10.1% | |

| 2000 | 1,380 | −24.6% | |

| 2010 | 1,270 | −8.0% | |

| 2020 | 1,156 | −9.0% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 1,343 | [5] | 16.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[33] 2020 Census[4] | |||

2020 census

[edit]| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 1,005 | 86.9% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 1 | 0.1% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 20 | 1.7% |

| Asian (NH) | 7 | 0.6% |

| Pacific Islander (NH) | 0 | 0.0% |

| Some Other Race (NH) | 5 | 0.4% |

| Mixed/Multi-Racial (NH) | 69 | 6.0% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 49 | 4.2% |

| Total | 1,156 | 100.0% |

As of the 2020 census, there were 1,156 people, and 627 households, and 284 families residing in the city.[35] The population density was 285.2 inhabitants per square mile (110.1/km2). There were 849 housing units. The racial makeup of the city was 88.8% White, 0.1% African American, 2.2% Native American, 0.6% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, 0.6% from some other races and 7.8% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.2% of the population.[36]

2010 census

[edit]As of the 2010 census, there were 1,270 people, 661 households, and 302 families residing in the city. The population density was 331.6 inhabitants per square mile (128.0/km2). There were 803 housing units at an average density of 209.7 per square mile (81.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 94.9% White, 0.2% African American, 1.8% Native American, 0.5% Asian, 0.6% from other races, and 2.0% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.4% of the population.

There were 661 households, of which 17.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 33.4% were married couples living together, 7.4% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.8% had a male householder with no wife present, and 54.3% were non-families. 44.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 1.88 and the average family size was 2.60.

The median age in the city was 48 years. 15% of residents were under the age of 18; 5.9% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 23.3% were from 25 to 44; 37.9% were from 45 to 64; and 17.8% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 52.5% male and 47.5% female.

2000 census

[edit]As of the 2000 census, 1,380 people, 669 households, and 341 families resided in the city. The population density was 365.4 inhabitants per square mile (141.1/km2). There were 817 housing units at an average density of 216.3 per square mile (83.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 95.87% White, 1.88% Native American, 0.36% Asian, 0.65% from other races, and 1.23% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.75% of the population. 29.8% were of German, 9.6% Irish, 9.5% English, 9.5% Norwegian and 8.7% American ancestry.

There were 669 households, out of which 20.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.7% were married couples living together, 10.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 48.9% were non-families. 40.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.01 and the average family size was 2.71.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 19.3% under the age of 18, 8.7% from 18 to 24, 27.3% from 25 to 44, 27.8% from 45 to 64, and 16.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42 years. For every 100 females, there were 93.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 92.6 males.

As of 2000 the median income for a household in the city was $28,641, and the median income for a family was $37,132. Males had a median income of $28,920 versus $18,807 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,673. About 6.9% of families and 10.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 19.4% of those under age 18 and 8.3% of those age 65 or over.

Education

[edit]Almost all of Deadwood resides in Lead-Deadwood School District 40-1. The city territory extends into Spearfish School District 40-2.[37]

In popular culture

[edit]- The Warner Bros. movie musical Calamity Jane (1953), starring Doris Day, was set in Deadwood City.[38]

- In 2006, a TV series of the same name was produced on HBO. It starred Timothy Olyphant as Bullock and Ian McShane as Swearengen.[39] The show was followed by Deadwood: The Movie in 2019.[40]

Notable people

[edit]Gold rush period (born before 1870)

[edit]- Granville G. Bennett (1833–1910), lawyer and politician

- Martha Bullock (1851–1939), frontierswoman, Seth Bullock's wife

- Seth Bullock (1849–1919), sheriff, entrepreneur

- Calamity Jane (Martha Jane Canary) (1852–1903), frontierswoman

- William H. Clagett (1838–1901), lawyer and politician

- Richard Clarke (1845–1930), frontiersman

- General George Crook (1828–1890), in 1876, pursued the Sioux Indians from the Battle of Little Big Horn, on an expedition that ended in Deadwood in early September, known as the Horsemeat March.

- Indiana Sopris Cushman (1839–1925), pioneer teacher in Colorado

- Charles Henry Dietrich (1853–1924), 11th Governor of Nebraska

- Dora DuFran (1868–1934), brothel owner in Deadwood

- Wyatt Earp (1848–1929), American investor and law enforcement officer

- E. B. Farnum (1826–1878), pioneer

- Samuel Fields supposed Civil War figure and prospector

- Arthur De Wint Foote (1849–1933), engineer

- Mary Hallock Foote (1847–1938), author and illustrator

- George Hearst (1820–1891), U.S. Senator from California

- Wild Bill Hickok (1837–1876), gambler and gunslinger

- Mollie Johnson (d. after 1883), madam in Deadwood

- Freeman Knowles (1846–1910), politician

- Joseph Ladue (1855–1901), prospector, businessman, and founder of Dawson City, Yukon

- Jack Langrishe (1825–1895), actor

- Kitty Leroy (1850–1878), gambler, trick shooter, and frontierswoman

- H. R. Locke (1856–1927), photographer

- Jack McCall (1852/1853 – March 1, 1877), also known as "Crooked Nose" or "Broken Nose Jack", gambler who murdered "Wild Bill" Hickok

- Valentine McGillycuddy, surgeon

- A. W. Merrick, journalist who published the first newspaper in Deadwood

- Madame Moustache (1834–1879), gambler

- Potato Creek Johnny (c. 1866–1943), gold prospector[41]

- Reverend Henry Weston Smith (1827–1876), early frontiersman and preacher

- Sol Star, entrepreneur, politician[42]

- William Randolph Steele (1842–1901), former resident, mayor of Deadwood, lawyer, soldier, and politician[43]

- Al Swearengen (1845–1904), entertainment entrepreneur[44]

- Charlie Utter (c. 1838 – aft. 1912), frontiersman who, with his brother Steve, led a wagon train to and set up shop in Deadwood, where they ran an express delivery service[45]

Later

[edit]- Jerry Bryant (died 2015), historian

- Charles Badger Clark (1883–1957), poet

- Mary McLaughlin Craig (1889–1964), architect

- Rowland Crawford (1902–1973), architect

- Gary Mule Deer (b. 1939), comedian and country musician

- Amy Hill (b. 1953), Japanese-Finnish-American actress

- Carole Hillard (1936–2007), Lieutenant Governor of South Dakota 1995–2003

- Ward Lambert (1888–1958), college basketball coach

- William H. Parker (1905–1966), former police chief of Los Angeles

- Dorothy Provine (1935–2010), actress and dancer

- Craig Puki, former linebacker for the San Francisco 49ers and St. Louis Cardinals

- Angelo Rizzuto (1906–1967), photographer

- Bill Russell (b. 1949), lyricist

- Bob Schloredt (1939–2019), former college football player for the Washington Huskies

- Jim Scott (1888–1957), played with the Chicago White Sox

- Jeff Steitzer (b. 1951), voice actor

- Chuck Turbiville (1943–2018), mayor of Deadwood and member of the South Dakota House of Representatives

- Philip S. Van Cise (1884–1969), Colorado district attorney

- Alfred L. Werker (1896–1975), film director

- Cris Williamson (b. 1947), singer/musician

Gallery

[edit]-

A photograph of Deadwood in 1876.

-

The Gem Variety Theater in 1878

-

City Hall in 1890, photograph by John C. H. Grabill

-

Deadwood, c. 1890s

List of mayors of Deadwood, South Dakota

[edit]Mayor McLaughlin called the first meeting of the Deadwood City Council to order on March 15, 1881.[46]

- Daniel Joseph McLaughlin; 1881–1882

- Kirk Gunby Phillips; 1882–1883

- Col. William R. Steele; 1883–1884 & 1894–1896

- Solomon Star; 1893 & 1896–1900

- Henry B. Wardman; 1893–1894

- James M. Fish; 1900–1901

- George V. Ayres; 1901–1902

- Edward McDonald; 1902–1906

- William E. Adams; 1906, 1914 & 1920–1924

- Nathan E. Franklin; 1914–1918

- Hobart S. Vincent; 1918–1920

- Dr. Frank Stewart Howe; 1924–1934 & 1936–1938

- Raymond L. Ewing; 1934–1936, 1938–1943 & 1952–1956

- Andrew B. Mattley; 1943–1948

- Edward H. Rypkema; 1948–1952

- Edward W. Keene; 1956–1962, 1964–1966 & 1978–1984

- Duayne W. Robley; 1962–1964

- Lloyd V. Fox; 1966–1968 & 1974–1976

- James E. Shea; 1968–1970

- Donald E. Ostby; 1970–1974

- Willard Pummel; 1976–1977

- Orville (French) Bryan; 1977–1978

- Thomas M. Blair; 1984–1989

- Bruce Oberlander; 1989–1995

- Barbara Allen; 1995–2001

- Francis Toscana; 2001–2013

- Charles (Chuck) Turbiville; 2013–2018

- David R. Ruth Jr.; 2018–present

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "SD Towns" (PDF). South Dakota State Historical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 10, 2010. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ^ a b "2023 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 17, 2024.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Deadwood, South Dakota

- ^ a b c "Explore Census Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 17, 2024.

- ^ a b c "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2023". United States Census Bureau. August 17, 2024. Retrieved August 17, 2024.

- ^ "Deadwood (SD) sales tax rate". Retrieved August 17, 2024.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. November 2, 2013.

- ^ Ullrich, Jan F. (2014). New Lakota Dictionary (2nd ed.). Bloomington, IN: Lakota Language Consortium. ISBN 978-0-9761082-9-0. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ "Discover the History of the Real Deadwood, South Dakota". deadwood.org. Archived from the original on June 7, 2015. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ a b Deadshot in Deadwood: Pettigrew Visits the Black Hills. Reprint of: The Sunshine State Magazine. Sioux Falls, SD: Siouxland Heritage Museums. 2002 [March, 1926]. p. 7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Deadwood: Topics in Chronicling America". guides.loc.gov. Archived from the original on May 3, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ "The Painted Ladies of Deadwood Gulch". Legends of America. 2003. Archived from the original on October 20, 2015. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ "Seth Bullock – Infamous Deadwood | Deadwood, South Dakota". Deadwood. Retrieved October 15, 2023.

- ^ "Illuminating The Frontier" (PDF). blackhillscorp. pp. 1–20. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- ^ Hilton, George W. (1990). American Narrow Gauge Railroads. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2369-9.

- ^ "Chinese". City of Deadwood. Archived from the original on June 3, 2012. Retrieved November 15, 2010.

- ^ Wong, Edith C.; et al. (2009). "Deadwood's Pioneer Merchant". South Dakota History. 39 (4): 283–335. ISSN 0361-8676.

- ^ David J. Wishart (2004). Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 140, 141. ISBN 978-0-8032-4787-1.

- ^ "Where East Met (Wild) West". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on August 21, 2010. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- ^ "Historic Wildfire in the Black Hills – Deadwood 1959" (PDF). National Fire Protection Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 7, 2008. Retrieved July 26, 2009.

- ^ "National Guard engineers end 77 years in Sturgis". Rapid City Journal. August 16, 2007. Archived from the original on April 4, 2018. Retrieved August 21, 2014.

- ^ "NHL nomination for Deadwood Historic District". National Park Service. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Deadwood gambling spurred change, but the town's evolution continues". Rapid City Journal. November 1, 2009. Archived from the original on November 8, 2009. Retrieved November 18, 2009.

- ^ "Reformers Stir Up an Old West Town" Archived June 6, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, by William C. Rempel, Los Angeles Times, July 20, 1980, p4

- ^ Perret, Geoffrey (May 2005). "The Town That Took a Chance". American Heritage. Vol. 56, no. 2. Archived from the original on October 4, 2009.

- ^ a b "Deadwood, South Dakota – Gambling, Historic Preservation, and Economic Revitalization" (PDF). USDA. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2010. Retrieved November 18, 2009.

- ^ a b "National Historic Landmarks Program: Deadwood Historic District". National Park Service. Archived from the original on January 6, 2008. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ Griffith, Tom. "Lights go out on Kevin Costner's Midnight Star in Deadwood". The Bismarck Tribune. Rapid City Journal. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ^ "NOW Data". National Weather Service. Rapid City, South Dakota. Archived from the original on July 20, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Deadwood, SD (1991–2020)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 14, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Deadwood, SD (1981–2010)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 14, 2023.

- ^ "xmACIS2". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 14, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Deadwood city, South Dakota".

- ^ "US Census Bureau, Table P16: Household Type". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 17, 2024.

- ^ "How many people live in Deadwood city, South Dakota". USA Today. Retrieved August 17, 2024.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Lawrence County, SD" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved September 27, 2024. - Text list

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (April 7, 2016). "Calamity Jane review – hugely enjoyable proto-lesbian musical". The Guardian. Guardian News & Media Limited. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ Singer, Mark (February 14, 2005). "The Misfit". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ HBO PR (March 21, 2019). "HBO Films' DEADWOOD Debuts May 31". Medium. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ "'Potato Creek Johnny' Joins Famed Pioneers Who Opened Up The West's Last Frontier". The Weekly Pioneer-Times. March 4, 1943. p. 1. Retrieved August 29, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Dary, David (2007). "Who was Seth Bullock?". True Tales of the Prairies and Plains. University Press of Kansas. pp. 117–120. ISBN 978-0-7006-1518-6.

- ^ "STEELE, William Randolph". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Archived from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Griffith, T. D. (December 8, 2009). Deadwood: The Best Writings On The Most Notorious Town In The West. TwoDot. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-1-4617-4754-3.

- ^ Straub, Patrick (2009). It Happened in South Dakota: Remarkable Events That Shaped History. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 31. ISBN 9780762761715.

- ^ "Former Mayors". cityofdeadwood.com. Retrieved August 17, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Deadwood Chamber of Commerce

- Deadwood Historic Preservation Commission

- Deadwood Digital Media Archive (creative commons-licensed photos, laser scans, panoramas), data from a DHPC/CyArk partnership

- Adams House and Museum Archived November 24, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- Enjoy Deadwood South Dakota Archived December 4, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- . . 1914.

- Deadwood, South Dakota

- South Dakota folklore

- American frontier

- Black Hills

- Cities in South Dakota

- County seats in South Dakota

- Cities in Lawrence County, South Dakota

- National Historic Landmarks in South Dakota

- Historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places in South Dakota

- National Register of Historic Places in Lawrence County, South Dakota

- 1876 establishments in Dakota Territory

- Populated places established in 1876

- Populated places on the National Register of Historic Places in South Dakota